In The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known Eli Siegel writes:

The pleasure we are proudest of, the emotion that is largest, arises from knowing the world as it is, wholly as it is, exactly as it is, tremendously as it is, poetically as it is, scientifically as it is, personally as it is.

That impulsion to know the world “as it is” makes for the large feelings men want most, and is in behalf of what Aesthetic Realism shows is our deepest desire, to like the world. It is also in steep competition with another desire Mr. Siegel asks about as he continues: “Do we get pleasure from how the world is, or because we use it cleverly for ourselves?” Using the world cleverly, manipulating people to do what we want and having victories over them, is contempt—the thing that stops a man from having the feelings he most wants.

Aesthetic Realism teaches men to distinguish between these two drives, enabling us to have the size and kind of feelings that make us proud, integrated, stronger.

The Debate in Miami Shores

I grew up in south Florida, the youngest of three boys. We had the kinds of things people think will make them feel good: a house with an indoor pool, new clothes each school year, summers at camp in the Carolinas.

Yet, with all this, most of the time I felt dull, contained and lonely. I was an average student, squeaking by in school with as little effort as possible. I didn’t know what Aesthetic Realism explains: there is an active drive in a man not to have feeling for anything. It’s based on the false ego logic that feeling for something else takes away from us—from what Mr. Siegel once called our “unconscious bank account.” In a class, Ellen Reiss asked me a great question on the subject: “Are you in competition with anything that might move you?” Yes I was.

As a boy, one time I was honestly excited was through an experiment for science class, comparing household disinfectants. I sterilized petri dishes in our pressure cooker at home, prepared a gelatin base in the dishes and learned how to grow the same bacteria in each one. Then I tested disinfectants to see which worked best, documenting the progress by photographing the dishes each day. Doing the experiment, I was in the midst of reality’s opposites—sameness and difference, potency and weakness, even good and evil—and I had a large feeling of pride.

But mostly I felt locked in myself and agitated. I had great difficulty sleeping, and never felt sure that my friends really liked me. I learned from Aesthetic Realism that these were payback for ways I had contempt. For example, I used my family’s good fortune to be a snob, feeling we were better than our neighbors. Feeling superior is attractive, but it is diametrically opposed to our hope to see meaning in the world.

I was a spoiled child and went pretty far with the feeling things should come to me, not from me. When I was 11 I wanted a new bike with a fancy metal-flake finish. My father said my bike, though an older style, was still in good shape and I could wait. This made me very angry. One day, I went behind one of the homes where there was a canal. I threw the bike in the canal, went home and said it had been stolen.

I got my new bike and felt triumphant. But to this day I feel very ashamed of what I did. My father worked hard to make money for a family of five, and went through a great deal about finances. Throwing that bike in the canal was like sticking out my tongue and saying, “I’ll get what I want and you can’t stop me!” That feeling is something no man can like himself for.

Steve Jobs, Modern-Day Innovator—What Kind of Feelings Did He Have?

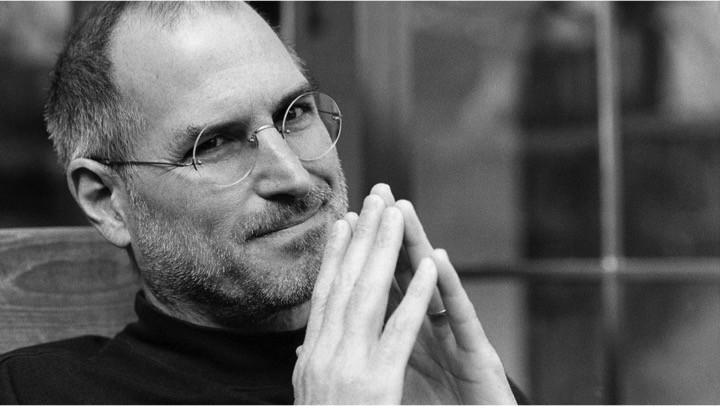

I am going to speak about aspects of the life and work of Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple who revolutionized a number of industries: personal computers, desktop publishing, music distribution, mobile devices. Steve Jobs oversaw the creation of products people love and I am one of them. He had a large feeling and a true instinct for how complex technology could be made easy to use. Yet, for all his achievements, Jobs was a tormented man whose feelings were a roller coaster of highs and lows. He was in a ferocious battle between respect and contempt—and contempt too much won out.

I am going to speak about aspects of the life and work of Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple who revolutionized a number of industries: personal computers, desktop publishing, music distribution, mobile devices. Steve Jobs oversaw the creation of products people love and I am one of them. He had a large feeling and a true instinct for how complex technology could be made easy to use. Yet, for all his achievements, Jobs was a tormented man whose feelings were a roller coaster of highs and lows. He was in a ferocious battle between respect and contempt—and contempt too much won out.

Steve Jobs was born in 1955 and was adopted by Paul and Clara Jobs, who raised him in Mountain View, California. Paul Jobs loved cabinetry and refurbishing cars, and “even cared about the look of the parts you couldn’t see,” said his son. Paul gave his young son his first taste for careful craftsmanship and electronics “and I got very interested,” said Steve.

I am quoting from the 2011 biography Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson, who tells how Jobs grew up in the heart of what later became known as Silicon Valley, where companies were developing advanced electronics. In high school, Steve joined the Hewlett-Packard Explorers Club, students who met in the company cafeteria one night a week when engineers discussed their latest projects. “I was in heaven,” he said:

I saw my first desktop computer there. It was called the 9100A, and it was a glorified calculator…It was huge, maybe forty pounds, but it was a beauty of a thing. I fell in love with it.

That early wonder about electronics came from the best thing in Jobs. Said Mr. Siegel, “Every science is a repository of feeling.” Yet right along with it, Jobs was making choices of a very different kind, which ran him his whole life. He knew he was bright and used it aggressively to look down on people and feel that most were incompetent at best. Isaacson quotes Jobs telling this boyhood memory:

“It was a very big moment that’s burned into my mind. When I realized that I was smarter than my parents, I felt tremendous shame for having thought that.”… This discovery [says Isaacson] made him feel apart—detached and separate—from both his family and the world.

The question is why did Jobs feel “tremendous shame”? The implication here is that shame was the inevitable result of thinking he was smarter than his parents, but I refute that. Another child might realize he had a certain intelligence and, using it to be kind, wouldn’t feel shame. It wasn’t the intelligence, it was the fact that he used it to feel disdainfully lofty and better than others. That’s what caused the shame and feeling “separate…from the world.”

There is a direct line from this early memory to what his later business colleagues describe. Jobs raked people over the coals mercilessly for perceived ineptitude, even trained himself to stare at people without blinking to make them squirm. Joanna Hoffman, who was on the team that developed the Mac, said:

He had the…capacity to know exactly what your weak point is, know what will make you feel small, to make you cringe…Knowing that he can crush you makes you feel weakened and eager for his approval.

When a man is after that kind of power, he has to loathe himself. There is a clear, kind logic Aesthetic Realism has articulated: If you build yourself up looking for the weakness of others, you cannot have feelings you’re proud of.

The Fight about Feeling

Michael White, a young New York City actor, handsome and amiable, had banked on his ability to charm people. Meanwhile, he was worried he didn’t have enough feeling about things, and wanted to stay on the surface. He told us he hoped to be a serious actor, and said he needed to see his father and girlfriend more deeply.

Aesthetic Realism shows that the purpose of acting is to see other people in such a way that one, in a sense, becomes those people; it shows that “you don’t have to be fettered to yourself. There is no limit to how much you can become other people!” Acting, we told Mr. White, is a way of liking the world itself by seeing the feelings of people with depth and accuracy. This idea thrilled him. And one day, some months later, he told us, “I had a really great time studying today for an audition,” because he got into the feelings of the character in new way. And where once he had told us, “I have doubted myself so much in love…my biggest fear is to be found out to be a fraud,” he now said he was having big feelings for his girlfriend Leslie Rae.

But he was puzzled, he told us, because “I have these scenarios in my mind when I’m on the subway or at work, and I get into arguments with people.” We asked:

Consultants: Do you think you’re having too much feeling these days? And the other side of you is saying, “You’re liking things too much. You’re giving yourself to the character in auditions. You’re having more feeling for Ms. Rae and your father. You have to get back in control.” Because somewhere you think having all this feeling makes you weak. Is that true?

Michael White: Yeah.

Cons. And do you think these pictures of arguments come up just because you’re having more feeling about the world? Is it coincidental, or is there cause and effect?

MW: I think there is. I think it probably has happened throughout my life and I haven’t been aware of it.

Cons. This tears people apart. It’s torn actors apart—why was I able to have that big feeling yesterday on stage, and I can’t feel anything today?

MW: Yes, I’ve felt that.

Cons. There’s an enormous pleasure in being able to despise, kick anything we want. And then there’s the pleasure of having the world inside one and trying to be fair to it. This fight goes on in mankind. We’re describing it so you can make better choices.

MW: Thank you.

Through Aesthetic Realism, Mr. White’s life flourished, and so did his acting. The feeling I have in bringing this education to a man is one of tremendous pride. I’ve seen before my eyes, men like Mr. White feel comprehended, changed, relieved and happy.

Technology, Feelings & the Opposites

Steve Jobs’ temperamental fits as a manager were notorious, but he had a different purpose—and feelings—when he spent days and months thinking about the smallest detail of a product in development and how it could be friendly for non-tech-savvy consumers.

Eli Siegel stated: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” This great principle is true about successful product design and explains some of Apple’s best sellers.

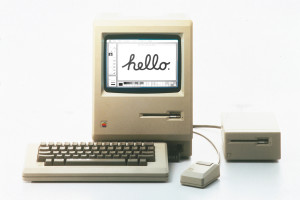

For example, the original Macintosh launched in January 1984. It was the first mass-market personal computer and it debuted two features to the general public, championed by Jobs, that are still in use today: a mouse and what is called a “graphical user interface” which, rather than being limited to horizontal rows of letters on a cathode display, allowed for playful icons, like a trash can, and free-form designs—like the “hello” you see.

For example, the original Macintosh launched in January 1984. It was the first mass-market personal computer and it debuted two features to the general public, championed by Jobs, that are still in use today: a mouse and what is called a “graphical user interface” which, rather than being limited to horizontal rows of letters on a cathode display, allowed for playful icons, like a trash can, and free-form designs—like the “hello” you see.

This first Mac was a new oneness in technology of the personal and impersonal, the animate and inanimate. Jobs insisted that it should look friendly, and as the design evolved it came to look a little like a human face, a being. At the product launch, he took it out of a canvas bag, turned it on, and in an “endearing electronic deep voice…[it said] ‘Hello. I’m Macintosh. It sure is great to get out of that bag.’” So an inanimate object was given feeling.

In an issue of The Right Of, Ellen Reiss writes something about computers that explains the success of the dear 1984 Mac—and the feelings of people booting up today:

The term personal computer itself is a oneness of opposites: in it, the word compute, which stands for impersonal mathematics, for strict, disinterested, cool calculation, becomes personal, warm; this important thing is in one’s home and is a means of furthering one’s so particular life.

A notable way the Mac was “personal, warm” was that it was the first computer to offer people a variety of beautiful fonts to choose from. Jobs had studied calligraphy and typefaces, and oversaw the selection of each one.

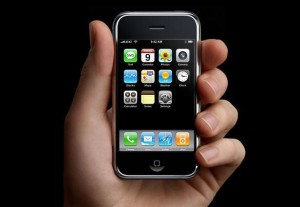

There was a new relation of surface and depth in the iMac of 1998, a “spunky appliance” with a translucent blue-green casing that let you see the components inside. 2001 saw the iPod, a dramatic relation of richness and compactness in a media player the size of a deck of cards (small at that time) that held an unheard-of 1,000 songs. And the 2007 iPhone was an industry landmark of simplicity and complexity, joining in one device a mobile phone, media player and web browser—with a touchscreen interface that felt natural for all three.

There was a new relation of surface and depth in the iMac of 1998, a “spunky appliance” with a translucent blue-green casing that let you see the components inside. 2001 saw the iPod, a dramatic relation of richness and compactness in a media player the size of a deck of cards (small at that time) that held an unheard-of 1,000 songs. And the 2007 iPhone was an industry landmark of simplicity and complexity, joining in one device a mobile phone, media player and web browser—with a touchscreen interface that felt natural for all three.

Jobs and his team made what had seemed like complicated, even cold technology feel welcoming. But right with it was Jobs’ own coldness and brutality as a corporate CEO. For example, he frequently refused to credit colleagues, including his top designer Jonny Ive, who worked themselves to the bone to get these products right, instead basking in the glory for himself at product launches where he was treated like a rock star.

Jobs and his team made what had seemed like complicated, even cold technology feel welcoming. But right with it was Jobs’ own coldness and brutality as a corporate CEO. For example, he frequently refused to credit colleagues, including his top designer Jonny Ive, who worked themselves to the bone to get these products right, instead basking in the glory for himself at product launches where he was treated like a rock star.

Then there is the cruel way products by Apple and other companies are manufactured by Chinese workers at Foxconn factories in Shenzhen and other cities. Wrote The New York Times:

Workers assembling iPhones, iPads and other devices often labor in harsh conditions…Employees work excessive over-time, in some cases seven days a week, and live in crowded dorms. Some say they stand so long that their legs swell…Under-age workers have helped build Apple’s products.

In 2010, with Jobs at the helm of Apple, 14 Foxconn workers jumped to their deaths from the roof of the Shenzhen factory.

In 2010, with Jobs at the helm of Apple, 14 Foxconn workers jumped to their deaths from the roof of the Shenzhen factory.

Like other companies today, Apple outsourced manufacturing to China because it couldn’t make products in the U.S. and reap big profits through cheap labor. Underlying this is the feeling: “I see you, employees, as a means of making money for me.” When that is your purpose, you can be brutal. Jobs was evasive and viciously cold to the torment of those Chinese workers. He once said with fake naiveté:

You go in this place and it’s a factory but, my gosh, they’ve got restaurants and movie theatres and hospitals…and swimming pools. For a factory, it’s pretty nice.

Jobs did not want to have feeling for those workers. It would have interfered with his ability to make profit from them.

What Kind of Feeling in Love?

Men want to have big, sweeping feelings in love. We hope through knowing a woman, talking with her deeply, being close to her physically, the whole world is closer, more exciting.

That is in competition with another feeling—“this woman should make me feel like a king.” We’ve wanted a woman to flatter us, hang on our every word. We’ve also wanted to manage her. I learned about that in an Aesthetic Realism class when I said I got angry with my wife, Meryl, because I thought she wasn’t using our computer properly and she didn’t seem to welcome my series of lectures on the subject. Asked Ms. Reiss:

ER: How much time should she do in prison for this?

BC: It was a stiff sentence. I got very mad.

ER: You’re still a little mad…Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning never argued about the computer.

Then Ms. Reiss asked about a feeling which has caused trouble in many homes and marriages:

ER: Do you think, Mr. Cooperman, you have used this computer to base your self esteem on in some fashion?

BC: I think so. I love the Mac.

ER: Even a wonderful thing like a computer can be used for bad importance. Do you think in some way you have had a second marriage to this computer? It can annoy one, but if one is adept at it you can manage it better than your spouse?

That was amazing—and true! I believe it’s central in the “computer widow” phenomenon, where men get engrossed in their computers and pay more attention to them than their wives. “A computer is easier than a woman, isn’t it?” asked Ms. Reiss. And then she put into words, in the form of a question, a feeling I aspire to to this very day:

ER: Do you think you are more important managing Meryl Nietsch or feeling, “She’s more complex than any computer, she doesn’t understand herself, but she has the whole world in her more richly than a computer does and I will spend my life trying to understand her”?

Yes I will! I love Meryl very much, a feeling that has grown with every one of the nearly twenty years of our marriage. I respect tremendously her careful study and high opinion of the education we present tonight. I count on her good will in wanting to know me, and am proud to feel I want to do the same in return.

In 2003, Steve Jobs was diagnosed with cancer. Over the next years, he met and spoke with people from the early days of Apple. Talking with Ann Bowers, you get a hint that he felt some regret:

…he looked at her and asked, intently… “Tell me, what was I like when I was young?”

“You were very impetuous and very difficult,” she replied. “But your vision was compelling.”

“I did learn some things along the way,” [he said.] Then a few minutes later, he repeated it, as if to reassure Bowers and himself. “I did learn some things. I really did.”

Steve Jobs died in October 2011. He never heard the straight criticism and radiant clarity of Aesthetic Realism and its explanation of the best and worst feelings in him, in men. He needed to know what Michael White was learning in his consultations. And so I end with a few simple sentences Mr. White wrote to us, which stand for what every man can feel: “Thank you for these consultations. I’m coming around. And I want to express my gratitude to Eli Siegel for this information, which is helping me in every instance of my life.”