In a historic class on September 14, 1975, Eli Siegel, Founder of Aesthetic Realism, read and discussed lines from what he has described as “one of the great poems of English literature,” Alexander Pope’s “An Essay On Criticism.” Written in 1709, the poem is, Mr. Siegel said, “still alive,” and he discussed it in a way that was completely new.

At 21, “An Essay on Criticism” made Pope famous because of the way he got so much into his tight, neat couplets. Mr. Siegel showed that what Pope is dealing with—what makes for a good poem and for good judgment as a critic—is something we need to learn from for our lives to go well.

Eli Siegel looked at many of Pope’s lines, explaining their beauty and value. He showed that a good critic needs to be aesthetic, to put opposites together, and we learned that central opposites in true poetry and good criticism are logic and emotion.

Mr. Siegel began by saying:

Mind happens to be geometry, and it happens to be the greatest anger. Tears come from mind, and also epigrams. Pope felt that poetry should be correct. What that means is still to be seen. Pope felt he could talk of what is in poetry in couplets, and as he does, one feels all is well with the world.

Pope wanted to see what makes a person’s judgment good and also what interferes. He writes about this in couplets which themselves are poetic and which people have enjoyed and been affected by for hundreds of years. “Within the couplet of Pope,” said Mr. Siegel, “is a lot of wonder.”

Alexander Pope’s Poem, “An Essay on Criticism”

“An Essay on Criticism” begins:

‘Tis hard to say, if greater want of skill

Appear in writing or in judging ill;

But, of the two, less dang’rous is th’ offense

To tire our patience, than mislead our sense.

Pope is saying it is less dangerous to “tire our patience” by writing badly than to judge badly and therefore “mislead our sense.” Then, he makes a comparison between how people feel about the accuracy of their judgment, and the accuracy of their watches:

‘Tis with our judgments as our watches, none

Go just alike, yet each believes his own.

Said Mr. Siegel, “We have to believe in our judgment because our judgment is ourselves.” Yet, he explained:

We are unsure of ourselves. One could ask in a kind way, “What do you think of yourself? Why do you think that way?” Every person who has gone through hearing questions is stronger because of it. To have criticism of oneself is fortunate.

And he said:

The art of self-criticism is the art man has gone for. There will be people in business who will write memos and dictate things…yet an executive has a gnawing notion that the person he is, he doesn’t like.

Hearing this makes me grateful for how Aesthetic Realism sees the subject of criticism. I am one of the people who has heard questions in consultations, and now in Aesthetic Realism classes with Ellen Reiss, and I am stronger because of them. I learned that we are always criticizing ourselves. But criticism today is not seen as what a person wants and needs most. It is seen as hurtful to the self, and people are told we need someone to praise and soothe us and build our self-esteem. Aesthetic Realism shows that the one way to like ourselves is to have this purpose in everything we do: to like the world on an honest basis and be fair to it.

What Is Good Taste?

“Criticism,” Mr. Siegel wrote in The Scientific Criticism in 1923, “is that action of mind, whose aim is to get the value of anything; and by value I mean size of power; and this power may be good or bad.” We learned that an important aspect of criticism is something everyone wants to have—good taste. In these next lines, Pope talks about the relation of being a true poet and having taste as a critic:

In Poets as true genius is but rare,

True taste as seldom is the Critic’s share;

Both must alike from Heav’n derive their light,

These born to judge, as well as those to write.

“Taste,” Mr. Siegel explained, “can be called the swift, immediate ability to value beauty.”

Eli Siegel himself was the critic to show that authentic poetry—of any style, form or century—arises from a person’s seeing reality in a way that is so honest and exact, the structure of the whole world is in the sound of the words, making for music. And that structure is the oneness of opposites. Commenting on opposites at the heart of Pope’s style of writing, Mr. Siegel gave this wonderful description:

The couplet here pleases definitely because of its energy and its trimness—like an evening gown that fits a girl very well, but at the same time, the fabric has texture and color.

This you can hear in the following lines, where Pope says most critics have at least the “seeds” or beginnings of the capacity for judgment:

Yet if we look more closely, we shall find

Most have the seeds of judgment in their mind:

Nature affords at least a glimm’ring light;

The lines, tho’ touch’d but faintly, are drawn right.

Along with those “seeds of judgment,” there are interferences to good judgment in all of us, and pointing to the two biggest, Mr. Siegel said: “Our desire to love ourselves, no matter whether we deserve it or not,” and our desire to “belong to the crowd.” Bad criticism, he showed, has to do with “ego and snobbery.” “Being in the swing, in the trend,” he said, “has made for a lot of corruption”:

When people get more interested in what others want to hear than what a thing is—that has made for a great deal of trouble.

He then asked this important question which people haven’t known the answer to, but have worried about: “What makes judgment weaker in a person?” The thing that makes a person’s judgment weaker, Aesthetic Realism explains, is contempt, “the addition to self through the lessening of something else.” One form contempt takes is competition, the desire to beat out other people and be above them. Pope describes this vividly when he says of some critics:

All fools have still an itching to deride,

And fain would be upon the laughing side.

And in these later lines, he talks about how some critics turned against the important poets and critics of ancient times from whom they had learned so much:

Against the Poets their own arms they turn’d,

Sure to hate most the men from whom they learn’d.

Here Pope is describing one of the worst things in self. It is the hatred of respecting someone else, feeling humiliated because you need to learn from that person. Eli Siegel himself was met with this ugly resentment throughout his life, and I saw studying this poem how much Pope detested that horrible, unjust emotion in people. Pope also described, with great feeling and respect, its opposite when he writes about critics who have a beautiful purpose: “The gen’rous Critic fann’d the Poet’s fire,/And taught the world reason to admire.”

In the next section of the poem, Pope describes with reverence how it is through nature that we can learn to be good critics because it is from nature that all true art arises:

Unerring Nature, still divinely bright,

One clear, unchang’d, and universal light,

Life, force, and beauty, must to all impart,

At once the source, and end, and test of Art.

Art from that fund each just supply provides,

Works without show, and without pomp presides:

Pope, Mr. Siegel explained, made clearer than anyone before him that nature “was always something to be followed.” Yet, Mr. Siegel asked, “what does it mean to follow nature?” And relating this to our everyday lives, he asked, “Do we act naturally? Once you ask the question ‘Am I natural?’ it’s useful,” he said. Aesthetic Realism explains that for a person to be natural is to be sincere. And to be sincere, we need to be like a good poem, to put opposites together such as logic and emotion, large feeling and precision.

Later, Pope describes a fight between two purposes that have been in critics:

For wit and judgment often are at strife,

Tho’ meant each other’s aid, like man and wife.

Here, Pope is saying that a critic’s desire to be witty and bright can get in the way of wanting to see something exactly. Then, pointing to opposites a true artist puts together—letting go and restraint—Pope makes a relation to a person riding a horse, a “steed”:

Tis more to guide, than spur the Muse’s steed;

Restrain his fury, than provoke his speed;

The winged courser, like a gen’rous horse,

Shows most true mettle when you check his course.

This, Mr. Siegel explained, “brings up a big thing”:

Is it natural to express or natural to abstain? Nature can tell you to do something with great zeal then go back from it….Where is art economy and where is it excess, overflow? Poetry can also be seen as the making of economy dazzlingly beautiful. The trimness of these lines is beautiful.

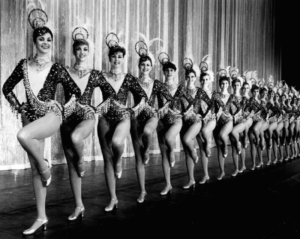

He said Pope’s couplets “are very tight,” and made a very surprising relation between the pleasure we get from them and from one of the most popular shows in New York: “Someone from the Bronx can be soothed by the Radio City Hall Rockettes. Pope’s couplets are a little bit like the discipline of the Rockettes.”

The large thing brought up by “The Essay On Criticism” Mr. Siegel explained is “what man wants to know most.”

Hamlet & the Desire to Know

Eli Siegel then read what he said was the “the most famous passage from Shakespeare’s Hamlet,” which is about the desire to know. It is from Act 1, Scene iv, when Hamlet meets the ghost of his father on the platform of the castle of Elsinore. Asked Mr. Siegel:

What is Hamlet trying to know through the ghost?… “How does some cause I don’t know make for you, father, and armor?”

Early in the scene, when his friends try to warn Hamlet to stay away from the ghost, Hamlet says again and again, “I will follow it.” And addressing the ghost he says:

Angels and ministers of grace defend us!–

Be thou a spirit of health or goblin damn’d,

Bring with thee airs from heaven or blasts from hell,

Be thy intents wicked or charitable,

Thou comest in such a questionable shape

That I will speak to thee;…

Hamlet shows a large desire to know when he says in some of the greatest lines of poetry:

King, Father, Royal Dane, O, answer me!

Let me not burst in ignorance; but tell

Why thy canoniz’d bones, hearsed in death

Have burst their cerements; why the sepulcher,

Wherein we saw thee quietly in-urn’d,

Hath oped his ponderous and marble jaws

To cast thee up again. What may ths mean…

Later, Hamlet asks why his father has come back in this form, “With thoughts beyond the reaches of our souls? / Say, why is this?”

Through this class, I saw how crucial it is for us to want to know what the world is. If you don’t, you can be sloppy, inexact, gush, try to impress through your wit, or be scornful, grudging, snobbish and try to make less of things.

Aesthetic Realism enables people to learn what it means to be a good critic of ourselves and the world. There is nothing more urgent for people to know, and so I conclude with these sentences which Mr. Siegel’s said at the end of the class:

If people knew how much they wanted to see what beauty is, they would use the phrase of Hamlet, “let me not burst in ignorance!”…Pope’s [couplets] are very trim, but they have beauty in them, pointing to the mystery of all existence….When people are very much affected by art, they have thoughts beyond the reach of their souls. You want to be as emotional as possible, and you also want to have judgment—to be as good a critic as possible—and don’t mind if Aesthetic Realism shows you they are the same.