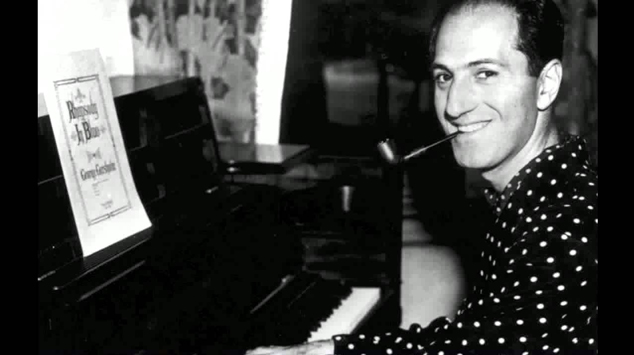

George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue was first performed by him in a concert with the Paul Whiteman orchestra on Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, February 12, 1924. We’re hearing a recording from 1927, with Gershwin himself at the piano and in an arrangement for jazz band created by Ferde Grofé, Whiteman’s chief arranger. The sound of this recording is rough, even a little primitive—different from a certain smoothness we’re used to hearing when this piece is played today. It brings out the sassiness and depth of this music as Gershwin originally conceived it. And we also get to hear George Gershwin himself playing.

In Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? Eli Siegel asks this question, which I see as central in explaining the Rhapsody:

Is there what is playful, valuably mischievous, unreined and sportive in a work of art?—and is there also what is serious, sincere, thoroughly meaningful, solidly valuable?—and do grace and sportiveness, seriousness and meaningfulness, interplay and meet everywhere…?

Ross Gorman’s Glissando

Right from the start, with that solo clarinet glissando played by Ross Gorman, there is an interplay of the “playful, valuably mischievous” and the “thoroughly meaningful.” It gets your attention immediately—each note is played so carefully, seriously, beginning with that low-register trill which changes on its way up into a slurred chromatic scale. That slur was actually Ross Gorman’s idea, and Gershwin loved it. Glissando means to slide from one note to another, and the clarinet is very playful here, even seems to laugh. But as we just heard, it can also wail.

Next, the clarinet does another glissando, but instead of continuing on to the melody, that melody is now played by a high trumpet with “wah, wah” mute. Repeating the melody shows that Gershwin wants us to take it seriously. But he’s joined it to yet another comic sound—that trumpet. And what follows? The very opposite: a bit of serious, meditative low piano—the first time we’ve heard the soloist, by the way. Then, the whole orchestra shouts enthusiastically; the piano responds with a longer solo; and the orchestra makes comic interruptions, including from the baritone sax.

I first heard this music as a young girl on Long Island. My mother would turn on the old Zenith radio while washing the dishes, and I stood in awe, listening to it. The way it’s both sassy and deep, sportive and profound, made me feel composed. How much I needed to know what Eli Siegel was teaching just 40 miles away in Manhattan in Aesthetic Realism classes about the relation of art and life: that every person is trying to put opposites together and that I could learn from this very music how I wanted to be.

How a Girl on Long Island Saw Playfulness

My “playfulness” had a very different purpose than Gershwin’s music. I could be serious as I studied music and art, but I was also wild and unreined in ways I despised myself for. Though I smiled sweetly, inwardly, I felt hard and tough as I made fun of people and laughed at them in my mind. I was sarcastic, especially with men. Years later, I was to learn from Aesthetic Realism that this contempt, building myself up through scornfully diminishing others, making light of their feelings, was the cause of my feeling inwardly heavy-hearted and mean.

In one Aesthetic Realism consultation, when I spoke about my worry that I couldn’t be serious for very long—that I liked dismissing things, my consultants asked, “Do you think that desire is in everyone?” “Yes,” I said. “Do you think you’ve gotten a lot of importance saying, ‘I can’t stand it here, I’m leaving.’”

MN. Yes.

Consultants. Would you like to give up the occupation of being a professional door slammer?

MN. Yes. I would! I think I have gotten importance that way.

Cons. So if you see people and things as having meaning you can respect, it is harder to dismiss them and justify saying, “I’m getting out of here.”

As I learned what it means honestly to like the world and to criticize the drive in me to make fun of things and to disparage, I became more truly lighthearted and more thoughtful. In Rhapsody in Blue—the high-jinks, the playfulness, and even a usefully mocking sassiness are not only in the same universe as warm, large, tender feeling but are at one with it.

Part of the reason Rhapsody in Blue is “valuably mischievous”—to quote Mr. Siegel’s phrase—are the speed and the teasing stop-and-start quality of the solo piano part. Is it sportive or profound? It’s both. And more than once, there’s an unexpected dissonant blare from the orchestra that seems to criticize what came before sharply.

Let’s hear it now, and I go to a more recent recording in an orchestral arrangement also by Ferde Grofé, with Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops, Earl Wild on the piano.

George Gershwin said he conceived the piece on a trip to Boston:

It was on the train, with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ty-bang that is often so stimulating to a composer….I frequently hear music in the very heart of noise. And there I suddenly heard and even saw on paper—the complete construction of the rhapsody, from beginning to end….I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America—of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our blues, our metropolitan madness.

Part of what we just heard has exactly that noise and “melting pot” quality: that dissonant “blare” on the brass, that noisy train-like sound, and that Latin-tinged rhythm. And in a moment, we’ll reach the grand, majestic section, which I think is the most beautiful part of the Rhapsody. Its largeness and lyricism seem to grow directly out of all the fun that came before. How Gershwin composed this is ever so fine; we hear a sound that goes out wide—yearningly—yet at the end of each phrase, as that grand arching melody reaches its longest notes, what do we hear underneath? A jazzy countermelody on French Horn, playful and sportive. This music is saying: “It’s the same world that has both the grand and the mischievous, and both are in behalf of respecting, not diminishing, reality.” Gershwin’s counterpoint between those two melodies resolves the conflict that practically ruined my life, between mockery and reverence, high jinks and seriousness.

After that grand melody, the music continues to search—building dramatically. As the Rhapsody concludes, we hear the most triumphant music in the entire piece. I’ll play this to end my paper. I want to say I’m very thankful to be studying in classes here at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation and getting the richest education in the world.