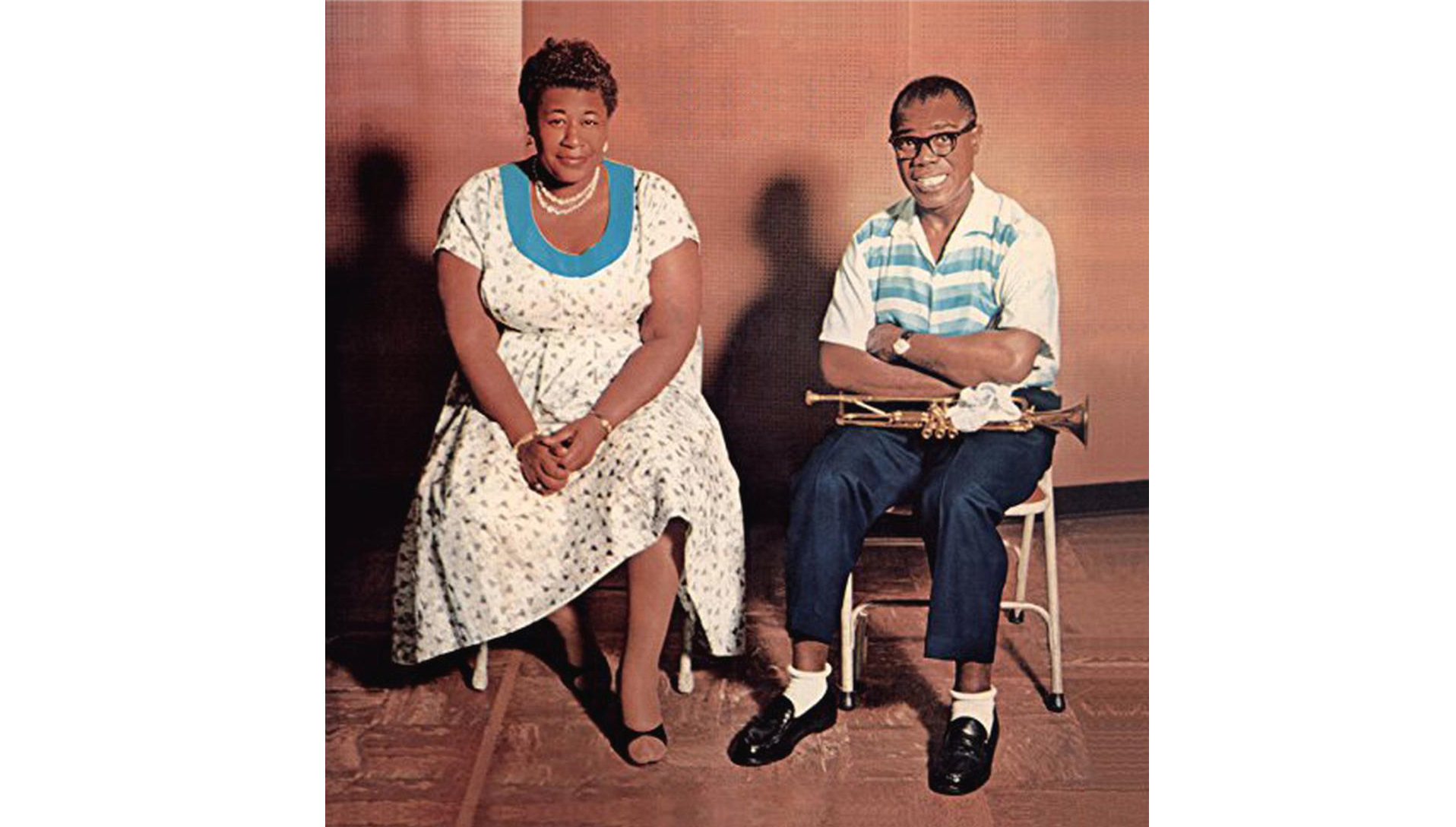

A recording I love is the great Louis Armstrong singing “They Can’t Take That Away from Me” by George and Ira Gershwin. His solo rendition comes in the midst of a duet with Ella Fitzgerald from the 1956 album Ella & Louis, one of my all-time favorites. And I think the very opposites we studied in the most recent semester of The Opposites in Music class at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation — Ease and Difficulty — explain why Armstrong’s rendition is so arresting, so moving.

Our text in the class was Eli Siegel’s essay, “The Graceful Effort; or, The Oneness of Ease & Difficulty in Art,”— a chapter from his book The Opposites Theory. In it he says, “There must be enough obstruction, resistance, somehow in a work to make that work likable deeply…. Reality resists as it beckons,” and he speaks about true art having both “love and struggle.”

That is what we hear in large measure in this recording. Ella begins the song sweetly and deeply. Her voice has a clear, warm, lyrical quality that is lovely. I’m going to talk mainly about Louis Armstrong’s singing, but here’s a taste of how Ella Fitzgerald begins. And you’ll hear that even while she accents something graceful, there’s also a little roughness in what she does with the rhythm — sometimes jumping the beat, sometimes holding back. As the critic Henry Pleasants says in his book The Great American Popular Singers, “She has an impeccable and ultimately sophisticated rhythmic sense.” Here’s her entire solo, with Louis playing trumpet in back of her, along with the superb Oscar Peterson quartet.

That is what we hear in large measure in this recording. Ella begins the song sweetly and deeply. Her voice has a clear, warm, lyrical quality that is lovely. I’m going to talk mainly about Louis Armstrong’s singing, but here’s a taste of how Ella Fitzgerald begins. And you’ll hear that even while she accents something graceful, there’s also a little roughness in what she does with the rhythm — sometimes jumping the beat, sometimes holding back. As the critic Henry Pleasants says in his book The Great American Popular Singers, “She has an impeccable and ultimately sophisticated rhythmic sense.” Here’s her entire solo, with Louis playing trumpet in back of her, along with the superb Oscar Peterson quartet.

Then as you just heard, Louis comes in, and there is the unmistakable sound of his voice. It’s like sunshine and cragginess, both at the same time. Isn’t that a little like ease and difficulty? My colleague, jazz pianist Alan Shapiro, has written that Louis Armstrong’s voice has the “roughness and grit of earth itself, and at the same time is so sweet, warm, tender.” When you hear Louis Armstrong, you can’t help but smile, and yet his voice is rough, it has obstruction, it isn’t just “pretty.”

The notable thing about this particular recording is how clearly you can hear the nuances of that roughness — the roughness and the feeling. He sings in a simple way, and it sounds like the microphone was very close up to him. This allows you to hear all kinds of subtle things going on in his voice — the dips, the crags, the sweetness, even the tugs in his throat. Here is the beginning of his solo, coming in just after Ella Fitzgerald has sung.

The notable thing about this particular recording is how clearly you can hear the nuances of that roughness — the roughness and the feeling. He sings in a simple way, and it sounds like the microphone was very close up to him. This allows you to hear all kinds of subtle things going on in his voice — the dips, the crags, the sweetness, even the tugs in his throat. Here is the beginning of his solo, coming in just after Ella Fitzgerald has sung.

To me, this singing has a beautiful raw quality; it’s as if you have a window into a person’s unvarnished feeling. Often, people think when something is raw it’s going to be difficult, not happy. That’s what I felt. But here the raw feeling is the same as sweetness and sincerity. In fact, I feel the sincerity of this singing is courageous, because it’s a person showing himself, not being falsely smooth, covered up.

We hear throughout this singing what Mr. Siegel said is in all true art: love and struggle. For example, you just heard the wonderful thing he does for a second on the word “key” when he says “the way you sing off key” — his voice slides down to the basement, and along the way we don’t know what key we’re in.

Now I’ll play some more of his solo and point to two other moments that are beautiful in how they put together ease and difficulty. First, the way he sings “life” so movingly in “The way you changed my life.” There’s pleasure but also some pain in the sound as he reaches for the note, and aren’t these — pain and pleasure — close to difficulty and ease? Then, toward the end of this section, when he sings the “No” on “No-o-o, they can’t take that away from me,” it’s a growl and a caress at the same time.

Are We Looking for a Oneness of Roughness & Ease?

Like many people, I preferred to stay away from things that seemed difficult. I wanted things to be easy, yet my notion of ease was wrong — because it didn’t include all the possibilities of the world, including its honest and beautiful roughness. And so, while I tried to find ease in various ways — from trying to make a neat, tidy world I controlled through having my apartment in perfect order, to taking drugs — I hardly ever felt at ease. And though I did my best to hide it, I was often terrifically agitated.

Two months after I began to study Aesthetic Realism, because of what I was learning about my deepest desire — to like the world on an honest basis — I already felt so different that I wrote in a letter to Eli Siegel, “I feel more comfortable in my own skin.”

The goodness of this recording is in how much Louis Armstrong welcomes difficulty and makes it one with delight and ease. We hear this in his trumpet solo, at the start of which he says, “Swing it boys.” He’s clearly enjoying that light swing rhythm of the quartet in back of him. At the same time, though he starts close to the melody, later he plays many unexpected notes, sometimes clearly dissonant ones, and with surprising, edgy rhythms. He doesn’t play it safe — he likes the feeling of being tossed around! And yet, he sounds so at ease, so relaxed.

The goodness of this recording is in how much Louis Armstrong welcomes difficulty and makes it one with delight and ease. We hear this in his trumpet solo, at the start of which he says, “Swing it boys.” He’s clearly enjoying that light swing rhythm of the quartet in back of him. At the same time, though he starts close to the melody, later he plays many unexpected notes, sometimes clearly dissonant ones, and with surprising, edgy rhythms. He doesn’t play it safe — he likes the feeling of being tossed around! And yet, he sounds so at ease, so relaxed.

Love — & What in Us Is Against It

Of course, along with Louis Armstrong’s and Ella Fitzgerald’s performances, there’s what this song is about. The person proudly says no one can take away the memories he has of the woman he cares for. There are ordinary memories, “The way you hold your knife,” and then deeper things, “the way you changed my life.” There’s both love and struggle as he says, “We may never, never meet again on that bumpy road to love / Still I’ll always, always keep the memory of…” That’s pain and pleasure as one.

What this song is about means a lot to me. I love my dear wife, Meryl Nietsch-Cooperman, very much. I cherish the chance to be with her and talk with her and hold her in my arms, and I look forward to the many memories we’ll be making as the years go on. I feel very fortunate for the education we’re getting from Aesthetic Realism about love, which is unprecedented, logical and magnificent!

Part of my education has been learning there was something in me that was actually against being stirred up by anything or anyone not me. Once, when I was going to sing a love song, “Annie Laurie,” in a musical presentation here, I was having trouble with the depth of feeling in it and I didn’t understand why. When I spoke about this in an Aesthetic Realism class, the Chairman of Education, Ellen Reiss, asked me:

ER: Do you like reverence or does it embarrass you? This song has grandeur and reverence.

BC: I think it embarrasses me.

And Ms. Reiss continued: “Do you think everyone is in a fight between great emotion and little emotion?” The answer, I’ve seen, is “Yes.” In my life I equated being at ease with keeping myself cool and intact.

At the time of this discussion, I was dating Meryl, and Miss Reiss asked:

ER: How much do you want Miss Nietsch to mean to you?

BC: She does mean a great deal to me and I want her to mean more.

ER: Does anything in you feel if you had a tremendous emotion that you would be a fool? You need to see there is that in you that feels, “I’m not going to be taken in by anything.” And you shouldn’t be. But one of the things a person can be taken in by is his own narrowness.

How true! What an education I was getting — and it continues. Said Ms. Reiss: “A person is being born right now. Would it be good for that person to have great feeling or little feeling?”

Louis Armstrong’s singing points to the answer to that question: that a person will never really be at ease unless he welcomes great feeling, including the honest roughness, the being shaken up, that’s in all great feeling. That principle is true about marriage, too. Through what we’ve learned from Aesthetic Realism, Meryl and I try to be good critics of each other — encouraging what is good in the other person, and saying where we think the other could be better. It’s not just smooth—as music shouldn’t be — and is sure is romantic.

I’ll end my paper the way the recording does as Ella Fitzgerald comes back in and then Louis Armstrong joins her, singing. At first, she’s high flying and he has rough, almost guttural punctuations underneath. They’re so different and they add to each other, need each other. Aesthetic Realism says, “Love is proud need.” And when he sings “The way you changed my life,” again I find it so moving. That statement surely stands for what I and so many others feel about Aesthetic Realism itself, which beautifully can change the life of every person.

I’ll end my paper the way the recording does as Ella Fitzgerald comes back in and then Louis Armstrong joins her, singing. At first, she’s high flying and he has rough, almost guttural punctuations underneath. They’re so different and they add to each other, need each other. Aesthetic Realism says, “Love is proud need.” And when he sings “The way you changed my life,” again I find it so moving. That statement surely stands for what I and so many others feel about Aesthetic Realism itself, which beautifully can change the life of every person.