I’m reporting on a historic lecture Eli Siegel gave on December 3, 1969, titled “What Does Poetic Music Go For?” He is the critic who has explained what makes for music in poetry—poetry of any time from Sappho to Shakespeare to Elizabeth Barrett Browning. “Poetry,” Mr. Siegel stated, “is the oneness of the permanent opposites in reality as seen by an individual.” And in this class, he spoke about why the study of music in poetry and what impels it is important for every person’s life. He said:

The criticism of poetry implies the full enjoyment of it. I think the trying to be fair to poetry is a wonderful thing to go after. It is exceedingly necessary because poetic music is the greatest tribute to honesty.

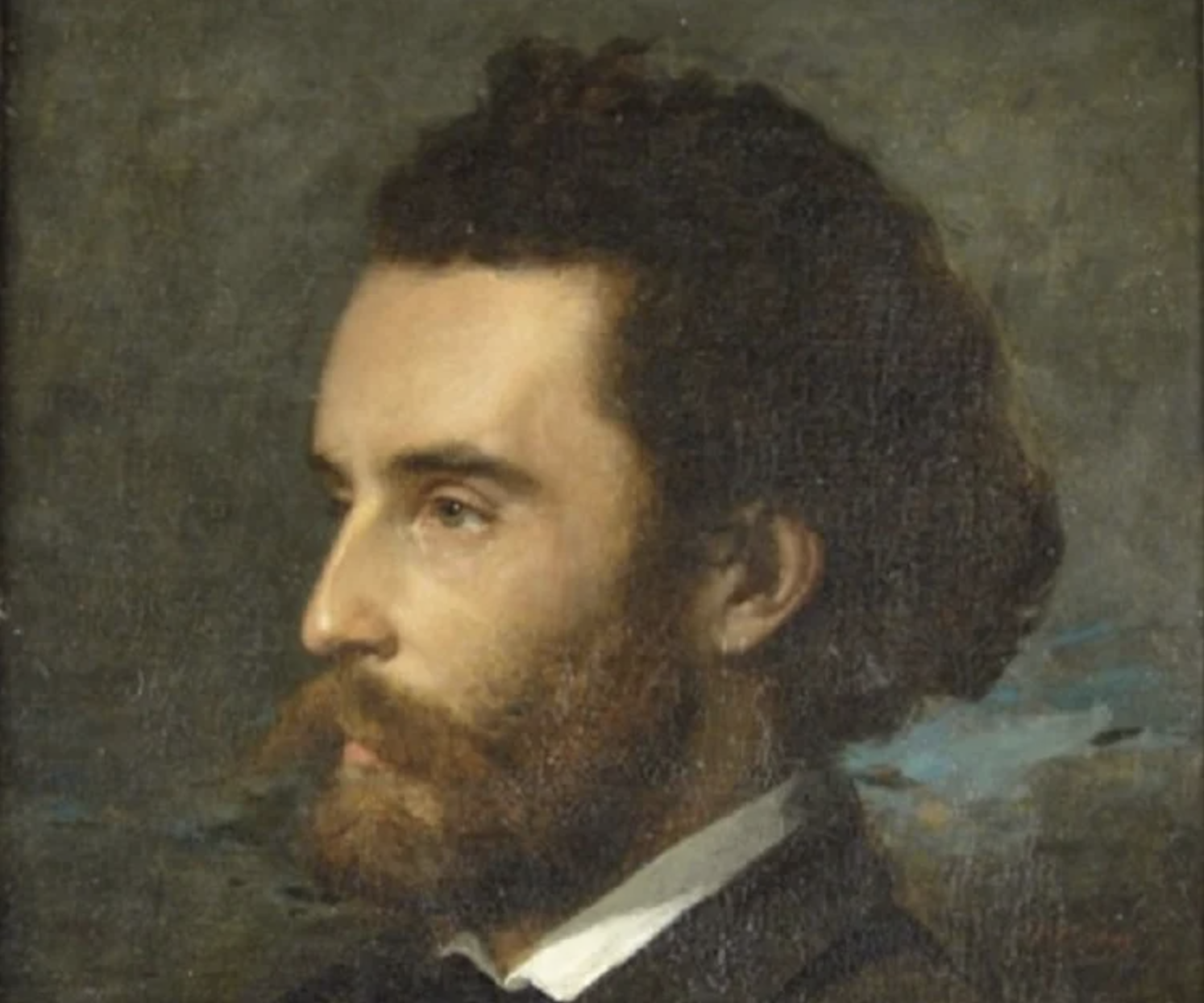

Alfred de Musset & Poetic Music

Mr. Siegel said that after a great deal of thought on the subject, the person he felt could be most useful in showing what poetic music is, is the French poet and writer Alfred de Musset, who lived from 1810 to 1857. In his poetry and prose, de Musset had both great feeling and precision and that combination, Mr. Siegel explained later, is what all poetic music goes for.

He discussed what he called “one of the great poems of its kind,” “À la Malibran,” about the famous 19th Century opera singer Maria Felicia Garcia Malibran, who stirred people tremendously both in Europe and America.

De Musset’s lines tell how she had a depth of feeling and sincerity at one with accuracy that made her immortal. “She was,” Mr. Siegel said, “one of the greatest singers of any time.” De Musset’s poem was written in October 1836, shortly after Malibran’s untimely death at the age of 24, and Mr. Siegel said, “There is no greater poem on a singer than this by de Musset.” He read each of its 27 stanzas in French, translating literally, and also read 17 short poems—translations he had made of portions of this moving work—which he called, “Little Poems from Alfred de Musset’s ‘À La Malibran.’”

De Musset, said Mr. Siegel, “is one of those persons who can clutch at your heart and clutch at your throat…. He’s alive.” He read these lines:

Où vibre maintenant cette voix éplorée,

Cette harpe vivante attachée à ton cœur?…

Ces pleurs sur tes bras nus, quand tu chantais le Saule,

N’était–ce pas hier, pâle Desdemona?

Mr. Siegel translated these lines as two short poems with titles:

Where Is that Harp?

Where trembles now this mourned voice,

That living harp at one with your heart?There Were Tears on Your Arms

Those tears on your naked arms, when you sang The Willow—

Were they not yesterday, pale Desdemona?

The Honesty of Maria Malibran

“We have nothing of Malibran’s voice,” commented Mr. Siegel, “we can only feel that de Musset was greatly moved hearing her sing.”

And there are these lines in which, Mr. Siegel said, “de Musset tells how Malibran is putting some notable opposites together”:

Heart of an angel and of lion, free bird in motion,

Mischievous child this evening, sainted artist tomorrow.

De Musset says other singers would pretend to have emotions, but Malibran simply couldn’t—and her honesty affected him very deeply. He speaks about her ability:

To…pour real tears on the stage,

When so many story tellers and famous artists,

A thousand times crowned, do not have any tear in their eyes…

We see de Musset’s tremendous respect for Malibran’s sincerity. Mr. Siegel described the quality of de Musset’s poetic music in one stanza as like the Spenserian stanza—“pulsating in neatness, pulsating in opulent exact measurement.” These are the opposites that he was showing in this class are central in all poetic music—emotion that swells, is boundless, and critical perception that is exact.

I think Mr. Siegel’s translation of another stanza conveys in English the “pulsating” that can be heard in the French:

This Makes Us Weep

What we weep rightly over your hastened tomb,

Is not divine art, nor its learned secrets:

Another will study the art you gave birth to.

It is your soul Ninette, and your naive grandeur.

It was that heart’s voice which alone comes to the heart;

Which no other, after you, will ever bring to us.

In a seminar at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation in New York City, consultant Carrie Wilson spoke of the life and art of Maria Malibran—of the intensity with which she was driven to sing, the beauty of her voice, and her tragic accident while riding fast on a horse. In these last stanzas, which are very beautiful, we can see that Malibran wanted to love something with all of herself—so much so that despite a serious injury, in the months following, she refused to rest and continued to sing at the theatre. De Musset writes:

Yes, yes, you knew it; you knew that in this life,

Nothing is good but to love, nothing true but suffering.

Each day in your songs you felt yourself paler.

You knew the world, and the crowd, and envy.

And, in that broken body concentrating your genius,

You saw, also Malibran dying.Die then! Your death is sweet, your task has been done.

What man down here calls genius

Is the need to love: everything besides that is empty.

And, since sooner or later human love is forgotten.

It is for a soul with grandeur and for a fortunate destiny

To leave life, as you did, in behalf of a divine love.

De Musset says Malibran gave herself utterly when she sang. This was the “divine love” he speaks of—which gives one “a soul with grandeur” and “a fortunate destiny.” “Was there a kind of love in the technique of Malibran?” Mr. Siegel asked, “What is the relation of love to a kind of profound accuracy?” “This,” he continued:

is what poetic music is about. These last two stanzas have closely to do with the title of this talk, “What does poetic music go for?” Every bit of poetic music has an attitude to the world and how one should see it. The music of poetry is the oneness of the utmost criticism and the utmost love.

As Mr. Siegel spoke of how poetic music is the oneness of unbounded feeling and exactitude of perception, and as I saw how these opposites were in both Malibran’s art and de Musset’s poem about her, I was tremendously moved. Like many people, I once thought having large emotions couldn’t be logical or accurate, and I am grateful to be learning from Aesthetic Realism how these opposites can be one in my life as I study the sincerity of poetic music. “Poetry,” wrote Mr. Siegel in an “Outline of Aesthetic Realism,” “is logic and emotion brought together so well, music ensues. Sanity is the oneness of unconfined emotion and perceptive precision.” And I want to say, Eli Siegel had that oneness of great feeling and critical exactitude all the time—he had the most beautiful relation of knowledge and feeling I have ever known.

Hippolyte Adolphe Taine on Alfred de Musset

To see further who Alfred de Musset was and what he was going for, we heard a passage from History of English Literature by Hippolyte Adolphe Taine, the French critic who taught at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. The passage is about de Musset himself and why he is so loved by the French people:

Such as he was, we love him forever: we cannot listen to another; beside him all seem cold and false…. From the heights of his doubt and despair, he saw the infinite…. He left his mark on human thought; he told the world what was man, love, truth, happiness. He suffered, but he imagined; he fainted, but he created…. There is in the world but one work worthy of man, the production of a truth, to which we devote ourselves, and in which we believe.

“[That] is a notable passage” Mr. Siegel commented, and he said of Taine, “There was no more famous professor of 19th century France.” He then read from The Complete Writings of Alfred de Musset, various passages of de Musset’s prose—about the Duke of Wellington, Christ, baked apples, an English dandy, the quality of evanescence in life, a caricature of a man from Peking. Even in his prose, we saw how de Musset was deeply affected by things and also had critical precision. For example, he writes about a tired horse:

Have you ever stopped in rainy weather to look at a cab-horse when, in spite of the fury of the winds, this pitiful, resigned creature waits patiently at the door of a house? A blow from the whip of his master is the one thing that can induce him to start on his jog-trot; until he feels that blow he stands perfectly still. His head bent down, he sadly submits to the pelting of the rain that drops from the eaves; perhaps at that sight, you can not help recalling the fine racehorse with fiery eye, which can not be held back and which poises on his nimble feet like a reed even on the straw of his stall. Are these two the same species?

De Musset also writes about a stream near Paris in a way that shows, Mr. Siegel explained, he “was interested in where things begin”:

I say, that when following the stream against its current, you never think whence comes this immense quantity of water, by what channels does it flow, what spring is its source? Why does it start in a corner of a lonely meadow, or the summit of a steep mountain, flow, and advance like a child at first, then a man, then an old man, toward the ocean which is its death.

I’m grateful to Ellen Reiss for taking seriously how Eli Siegel explained poetry, and for her joyous, warm scholarship as she teaches The Aesthetic Realism Explanation of Poetry class. In the discussion following the lecture, she described the state of mind of a person when that person writes a true poem:

A person feels at that time that justice to an object—justice to the world itself and how it’s made—is the same as taking care of oneself. The person wants to be so just, the whole world gets into the sound. The universe does provide a chance of feeling that a person can be himself fully by being fair to what’s not himself.

Concluding this beautiful lecture, Mr. Siegel read a short poem of de Musset in which, he explained:

De Musset says that the world can be endured if there’s music that you can like and also a face that is beautiful. The poem is one of de Musset’s small lyrics that seems to be like a breath. It’s called “Chanson.” This is Mr. Siegel’s literal translation:

When one loses through sad occurrence

His hope and gaiety

The remedy for the sad and melancholy one

Is music and beauty.

A beautiful face can do more than an armed man.

Learning about poetic music through what Eli Siegel said about the work of Alfred de Musset was one of the greatest experiences of my life! “The music in poetry is ever so important,” he said, “because it shows that a logical statement can be musical. If a thought-out statement can be musical—what good tidings that is.