In his definitive lecture, “Mind and Importance,” Eli Siegel said:

If you are important because you feel that what’s real is important, that other people can be important…then your importance is good…Every time we make ourselves truly important, we are making something besides ourselves important, whether we know it or not.

This is utterly different from what I once thought. Real importance arises from being true to our deepest desire—to like the world different from us. Yet every person, I learned, is in a debate between “making something besides ourselves important” and making other things less, which is contempt. In “Mind and Importance” Mr. Siegel describes this state of mind:

You are the only important thing in sight and you are going to get your importance even if other people are made unimportant.

Growing up, I had no idea I had two completely different ways of trying to be important. For instance, when I was seven I planted seeds to grow zinnias by the side of our house. I read about how far apart to put the seeds and how much to water them, and I was so excited when the sprouts first burst through, out into the light. I tended them and soon there were many tall colorful flowers, and I felt proud.

But mainly I thought I would be important if I made a lot of money and was “in” with the right people. I wanted to be “the most important thing in sight” and I was scheming. In seventh grade I ran for president of my homeroom class, and on election morning I passed out candy to everyone so they would vote for me.

Then in college I sold vacuum cleaners. I remember pushing the Jenkins family to buy this expensive vacuum cleaner. They were poor and lived in terrible conditions, and the vacuum cleaner was the last thing they needed to buy. But I didn’t care—I just wanted that signature on the contract, and my commission. I will always feel ashamed of this; it stands for what I learned is like math: every time we go for importance based on contempt we are cruel to other people and we cannot like ourselves.

Aesthetic Realism is great because it educates people to choose the one basis of importance that has us respect ourselves—to like the world. Eli Siegel, Aesthetic Realism and Ellen Reiss have done that for me and I love them for it. I had led a selfish, constricted life and I felt more empty every year. Is my life different now!—happy, rich and useful, and I love the work I am honored to have as an Aesthetic Realism consultant.

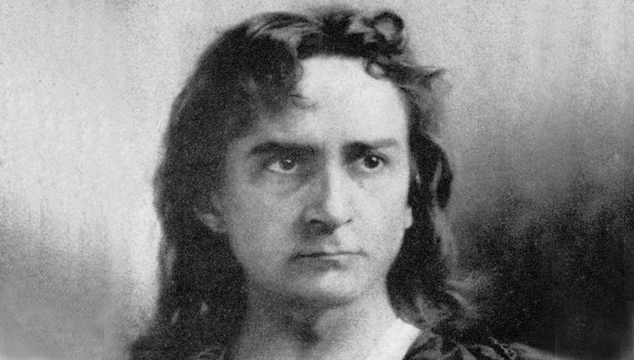

To show what true importance is and what interferes, I will speak about my own life and aspects of the life of the great 19th century American actor, Edwin Booth. Edwin Booth is truly important because in a large, beautiful way he saw importance in what was not himself, particularly the plays of Shakespeare. Booth was best known for his portrayal of Hamlet—pictured at right—acting this role with a quiet fervor that had a tremendous effect.

Eli Siegel, who I believe was the most important critic of the drama, comprehended the meaning and beauty of the works of William Shakespeare. In his critical masterpiece, Shakespeare’s Hamlet: Revisited, Mr. Siegel explained this play and its immortal hero. Mr. Siegel loved Hamlet and knew the history of how actors had performed the role. So it has great importance that he wrote in The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known#212: “Edwin Booth is our most meditative Hamlet, and, everything considered, our most successful.”

Two Ways of Being Important, Early

Every person, Aesthetic Realism explains, has an attitude to the world, and this begins with how we see the first representatives of the world we meet: our parents.

Edwin Booth was born November 13, 1833, in his family’s log cabin in rural Maryland, the seventh child of Mary Ann and Junius Brutus Booth. A large drama of Edwin Booth’s early life was his relationship with his father. Junius Booth was the preeminent American actor of his day, best known for his King Lear and Richard II. He had a true care for the drama and literature, and his manner was outwardly rough and bold.

But the life of an actor traveling across America in the mid-1800s was tough, and it took its toll on Junius Booth. He began to drink heavily, and had bouts of rage. Then three of his children died in a short span of time, and from then on Junius Booth was, at times, on the brink of insanity.

Young Edwin was “grave, thoughtful…and especially reticent,” writes the critic William Winter. At thirteen he was sent to keep his father company on the road and to stop him from drinking. In her biography, Prince of Players, Eleanor Ruggles writes:

It steadied [the elder Booth] to re-enter his dressing room after a performance and find Edwin there, wan, rather taciturn, but instantly and silently solicitous of his father’s comfort…it was this son’s voice, a quiet voice, that could recall the father when Booth was wound about in melancholy or lost in frenzy.

Edwin Booth went on the road with his father for years. He saw his father’s life as important, worthy of his steady care. Yet I believe he felt something else, too. In The Right Of #137 Eli Siegel writes about Hamlet and his father; as he does I think he describes what Edwin Booth felt:

A father is a most dignified being…but as a person, he can have frailties a knowing or perceptive child may see…Hamlet, like many children, is between seeing his father with respect and as confused, non-admirable.

I think Edwin Booth felt superior to his father’s jaggedness and troubles, and made an unconscious choice early that he would take care of himself by a refined, reserved approach to the world. This was really a choice to have contempt—to feel important being aloof from what he saw as the rough edges of a messy world.

My life growing up in suburban Miami in the 1960’s was very different from Edwin Booth’s. Yet I too made early choices to have contempt. I saw that my mother and father were disappointed with each other, but I didn’t try to know what they felt, to be kind—I didn’t feel that would make me important. Instead, I used what I saw to be superior to these two grown ups and people as such.

I used my family to be a snob. When my father’s company gave him a Cadillac, I liked knowing the neighbors saw that car in our driveway. From then on I pushed him to buy fancy cars even though he didn’t want them. This was so mean; my father worried a lot about money and supporting a family of five. I am so grateful Aesthetic Realism criticized my contempt; I was able to be a kind son to my parents for the first time in my life.

Acting Is for Man’s True Importance

Aesthetic Realism taught me that art, including the art of acting, makes us truly important. In his great lecture “Aesthetic Realism as Beauty: Acting,” Mr. Siegel said:

Th[e] possibility of loving the world that we have through acting is much worthy of study…Everybody wants to be himself, and that means being other things besides himself. And in order to be other things besides ourself, we must put aside our self while still having it. As we do this, whether we go on the stage or not, we honor the principle of acting.

Edwin Booth first acted with his father in Shakespeare’s Richard II, at the age of sixteen. From then on father and son acted together frequently, but in 1852 Junius Booth died. Edwin was despondent for months. Then he began to act on his own and soon he became popular. Booth was dashing and thoughtful. Eleanor Ruggles writes:

People wheeled in their tracks for a sight of him tearing to rehearsal…on a high, white horse…he had a mass of black hair and a face like a cameo.

At twenty-three Edwin Booth met the sixteen year old actress Mary Devlin as they played Romeo and Juliet. Mary Devlin saw something very fine in him, and encouraged him to be serious in a new way. Years later their daughter Edwina wrote: “He has told me that she was always his severest, and therefore his kindest critic.” I respect this in Mary Devlin. She worked with her husband to come to a style of acting truthful to who he was. She once wrote to him:

You must not forget to tell me of your studies; they interest me alike with the movements of your heart. Dear Edwin, I will never allow you to droop for a single moment; for I know the power that dwells within your eye.

Mary Devlin and Edwin Booth were married in 1860 on West 11th Street in New York City. Unknowingly, like men and women everywhere, they had two purposes in their marriage, which only Aesthetic Realism explains—one, a true care for the world that showed in their seriousness about acting. But they also used each other to be exclusive and superior to people. Eleanor Ruggles writes that “the young couple held the world at arm’s length.”

I also think Booth used his wife’s devotion to feel he didn’t need to know her, to see her feelings as important. I am tremendously grateful for questions Chairman of Education, Ellen Reiss, so kindly has asked me in Aesthetic Realism classes, such as: “Do you want to know a woman for the means of knowing yourself, or getting as much approval as possible?” “Do you want a woman to be as good as she can be or serve you in some way?”

My purpose was the second—I wanted a woman to make me the most important thing and this made me mean, which I regret. I am so grateful to Ms. Reiss and Aesthetic Realism for what I am learning about love, what it means to really care for a woman—to have good will. And it makes me so happy to continue learning in my nine-year marriage to Meryl Nietsch-Cooperman. I feel important trying to know who Meryl is, learning from her straight and humorous criticism of me, studying together in classes with Ms. Reiss where we learn about ourselves and the world. Aesthetic Realism is beautiful sanity about what makes a person important and love, and I want men and women everywhere to know it.

The Opposites Make One Important

In “Mind and Importance” Eli Siegel says the word “important” means “that which carries something to us,” and continues, “we’re important because we carry much weight.” Booth’s acting took on increasing weight and he had a powerful effect.

For example, when Julia Ward Howe attended a performance in Boston of Richelieu, upon Booth’s first lines she leaned over and whispered to her husband, “This is the real thing!” And Eleanor Ruggles writes about Booth’s acting Sir Giles Overreach in Massinger’s A New Way to Pay Old Debts, in the death scene:

As his body thrilled in a horrible spasm and pitched face forward to the floor, the whole length of it seeming to hit the stage at once, and there continuing to twitch and quiver, so strong a sense of evil poured out of it that half the [audience] turned away their eyes . sick and shaken.

In time, along with this passion, Booth’s acting had a terrific sense of control—a quietude invested with such great feeling and meaning, it was arresting.

Eli Siegel stated the most important sentence about beauty and what people are hoping for in their lives in this great principle: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

In The Right Of #212, subtitled “All the Arts,” Mr. Siegel writes greatly about the opposites of passion and control, and he speaks of two American actors. Edwin Forrest, a contemporary of Booth’s, “generally stood for passion in the art of acting,” writes Mr. Siegel, and “Another Edwin, Edwin Booth… represented meditation.” One critic said that quality in Booth, his quiet intensity, made him seem in the soliloquies to speak “from inside the listener.” Booth began to act with a simplicity that was new in tragedy—he seemed more like a person one might meet. Yet he was never ordinary at the expense of grandeur; he conveyed a great sense of humanity and the soul of man.

At the Winter Garden Theatre in New York, Booth produced a series of classical revivals unlike anything that had been. He played Hamlet, Othello, Shylock, Iago, Romeo. He was impelled to have people like Shakespeare, and they did—these sumptuous productions were the hit of the day. Booth insisted on using the original Shakespearean texts, which in the 18th century had been altered and cut into versions untrue to Shakespeare. All his life Booth had a reverence for Shakespeare. He once wrote that Shakespeare “says scarcely anything that is not true and good.” How much he would love Eli Siegel, the person who understood Shakespeare and humanity; and who, I’m so grateful to say, taught me to love Shakespeare honestly, too.

The Fight about Importance

In “Mind and Importance” Eli Siegel explains the thing in us that is against being truly important. I believe this explains a fight which, unknown to him, came to a head in Booth just at the time of his greatest success:

We have to meet this thing which says, any time you say something is good or important which is not you, you are taking away from your unconscious bank account.

Booth loved acting and also had a deep care for his wife. Yet I think he began to feel this care for what was not him took away from his “unconscious bank account.” Also he likely missed something from Mary Devlin who both revered him and had a tendency to patronize him, referring to Edwin as a “genius” with an “untaught mind.” Eleanor Ruggles writes that Booth’s thoughts “turned inward,” he began to drink and even act under the influence. “No one can imagine the call of that desire,” he said. “When it engulfs me I could sell my soul…for just one glass.”

In 1863 Mary Devlin, who had given birth to their daughter Edwina, became ill with consumption and went to their home in Massachusetts to rest. Booth, acting in New York, seemed not to be aware of his wife’s condition, which became grave. He was drinking so heavily that when three telegrams accumulated on his dressing room table about Mary, each increasingly urgent, he didn’t see them. Finally realizing what was happening, Booth rushed to Massachusetts, but it was too late—Mary died just hours before he got there.

His regret was searing. He wrote to a friend “My grief eats me!”:

“My conduct hastened her death, when she heard that I…was lost to all sense of decency and respect.” “I feel now how mean, how thoroughly nothing I am.”

The shock of his wife’s death and the intensity of his guilt did, in time, make for a large change in Edwin Booth. He never drank that way again. From what I read it seems Booth used his regret about her death to be less selfish and more fair to the world. He said he didn’t value Mary while she was alive, the good effect she had on his work. And he became determined to honor this now.

One year later Edwin Booth acted Hamlet with a beauty, an utterness that electrified audiences. Eleanor Ruggles writes:

From his first entrance upstage left every eye was riveted on that forward-drifting…elegant…figure in…black with the dark hair hanging to the shoulders. [In the “to be or not to be” soliloquy]…The audience sat rapt…while the six words on which the actor had lavished as many weeks of labor seemed not to be spoken to, but within each separate consciousness…He was fire and elegance as he fenced with Laertes…[Then, dying]…in Horatio’s arms, [he] breathed his last words in tones…invested with sublime pathos… There was no…applause until the orchestra [began to play]…and snapped the charm.

This was Booth’s most stunning success. Said one critic, “He did not act Hamlet—he lived it.”

A National and Personal Tragedy

A great tragedy in American history was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by Edwin’s younger brother, John Wilkes Booth—at left in the photo. This was taken when the three appeared in Julius Caesar in 1864, the only time they acted together.

Lincoln’s assasination came from one man’s horrible notion of importance taken to the extreme, and which is the most ruthless thing in everyone: if anyone else is important I am less—I have to be “the only important thing in sight.”

John Wilkes Booth, an actor himself, was increasingly furious at Edwin’s success which was far greater than his. And the brothers disagreed intensely about which side was right in the Civil War, John Wilkes Booth being fiercely for the South. He felt important making an entire race—black people—unimportant. Lincoln stood mightily for opposition to this; when it looked as if the opposition might become law, John Wilkes Booth became infuriated. Eleanor Ruggles writes:

On April 11th…he…listen[ed] to Lincoln speaking from a balcony in favor of giving the ballot to the Negro…”Now, by God, I’ll put him through!”

Three days later, he did.

The whole world was shocked and Edwin Booth’s life was shattered. Not knowing at first who was responsible, government officials arrested most members of the Booth family. Edwin Booth—who cared deeply for Lincoln and, in fact, had once saved his son’s life—went into hiding and said he would never act again. Eleanor Ruggles writes that afterwards “a little of the savor of life came back to him—but not the whole, ever.”

I feel so much for Edwin Booth. I am sure he would have been so grateful if he could have known what Aesthetic Realism explains, that with a terrible, unspeakable tragedy a person can confirm an inaccurate opinion of the world come to years before. Edwin Booth, I think, felt more than ever the world was messy, cruel and meaningless—a place in which he should act genteel but essentially stay away.

Yet it is greatly to Booth’s credit that he did continue to act and even built the Booth Theatre on 23rd Street, staging again productions of Shakespeare with unparalleled beauty. He founded the Players Club for actors, still on Gramercy Park, where he lived his last years. But Booth seemed to get old very fast, and often spoke of wanting to die, which he did at the age of 60 in 1893.

Edwin Booth’s life and art cry out for the need of people to know Aesthetic Realism. He needed to know the most important thing in him that made for true art: his desire to like the world. And he needed to know the greatest interference to this: contempt.

Aesthetic Realism has enabled me to use my mind to like the world, to be honestly interested in people’s lives, in history, literature, the drama and to feel passionately about what is happening in the world. This has given my life true importance, happiness, sweetness and dignity, and I want everyone to know it.