Like many men, I thought I would be sure of myself if I made a lot of money, had nice clothes, a substantial career and impressive friends. Though I tried to act like a “nice guy,” I went after these things aggressively. But even as I got many of them I felt empty, and with every year, less sure of myself.

I learned from Aesthetic Realism that a man will be rightly sure of himself when his purpose is to try and be fair to people and the world itself. This is good will, and it’s not a soft thing. Good will is a beginning, organic drive in a man, and if he is untrue to it, he’ll be deeply unsure no matter how much he swaggers and tries to cover it up. Eli Siegel has defined good will as “The wish of a person that good things happen to things—things include people—with the desire to know what those good things are.” And he explained:

The having of good will as not contrary to logic or care for self, is the greatest mental attainment that is possible. This is a corollary of the Aesthetic Realism belief that liking the world on an honest basis, without smooth deception of oneself, is the purpose of man and of life.

Many of the ways I tried to be sure were against that purpose. I wanted to be better than other people—smarter and more savvy. This, I learned, was contempt, and I’ve seen that what I really wanted was so different.

Knowing the World Versus Using It

As a boy and young man, I loved studying singing and dancing. Later at Syracuse University as an acting major, some of the times I felt best were working on a role, trying to understand a character. I liked thinking about what the character’s life was like before we see him in the play, how did he move and talk?

In my freshman year I was cast in Bertholt Brecht’s play Galileo as a crippled man dressed in rags in a large street scene with many people. My legs were tied behind me, and, lying on the ground, I had to pull myself along with my hands begging for food, trying not to be stepped on or hurt. Though it was a small part and seemingly lowly, I loved it and had a certain confidence during rehearsals. I liked trying to become this man whose life was so different from mine, who was forced by circumstances to be humble.

But in my everyday life, I went after another kind of sureness, based on arrogance. As the youngest of three sons in suburban Miami Shores, Florida, my parents made a lot of me, and I came to feel I was the best boy in the neighborhood—better than my two older brothers.

I was the “good” one and I milked it. Also, I was sure that the Coopermans were one of the better families in Miami Shores. We had money, my father had a Cadillac, and I thought of us as the Jewish Kennedys. By the time I was six or seven, I walked around feeling like a prince—smugly convinced that my place in life was above that of most people. Though I wouldn’t have put it just this way, I equated being sure of myself to looking down on other people, having contempt for them, and this had terrific consequences.

I often felt agitated, bored and very separate. And from as early as I can remember, I had great difficulty falling asleep—something that did not change until I studied Aesthetic Realism. Sometimes I secretly took my mother’s sleeping pills to knock myself out. Then when I did sleep I often had nightmares, and remember once yelling out for my father to come to my room, because I was practically frozen in bed with fear, convinced someone behind the chair was trying to get me.

I learned from Aesthetic Realism that you cannot have contempt without a kickback. In The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, Ellen Reiss explains:

The underlying doubt, the underlying uncertainty that we can have, unarticulated yet poking and sometimes gnawing and thrusting within us, in relation to any aspect of our lives is this: Am I liking the world more through this thing I’m in the midst of—or am I using it to dislike the world? People haven’t known that this unspoken question is behind the nervousness or unsureness or perhaps sudden sinking they may feel.

When I graduated from college and needed a job, I worked as a condominium salesman for my father and brother who owned a retirement development in Sunrise, Florida. Once I began I was ambitious to be a hotshot salesman. So while acting affable to the retirees who came to look at the apartments, I was conniving in my thoughts, seeing each one as a potential sale who would make me money and also make me look good. I remember laughing it up as I told my father and brother how I pounded on the walls in the model apartment to show one elderly couple how solid they were. I thought I was so clever, and they were so gullible.

I saw no relation between this contemptuous way of thinking about people and the fact that I hated my life. I was living alone in one of the model apartments, and was excruciatingly lonely and unsure of myself—so much so that I often smoked pot in the morning before I went into work, feeling I couldn’t function otherwise.

A college friend had told me about Aesthetic Realism, and one sunny afternoon in 1976, from the sales office I called the Aesthetic Realism Foundation and asked to have consultations. I told the young woman at the other end of the phone that I had to learn to like myself first, and then I would feel at ease and confident with other people. She said Aesthetic Realism explains it’s just the opposite—you have to like the way you see the world and other people first, and that will have you like yourself. The logic made such sense, but I had never heard anything like it before.

Soon I had my first consultation, and was asked at one point: “Are you an agonized mingling of sureness and unsureness?” Yes, and hearing that put into words I felt understood.

I remember, too, that soon after this consultation was the first time I actually saw I had contempt. I was in the Broadway/Lafayette subway station and asked someone for directions. The directions turned out to be wrong, and I muttered under my breath, “God damned New Yorkers.” A second later I thought “That’s it!—that was contempt—you just panned a whole city of people because one man made a mistake.” Seeing this I wanted to jump for joy!

Learning how contempt worked in me, and also getting a tremendous education in what it means to respect people, to have a wide interest in the world, I began to feel a sureness I never had before. Just a few months later I wrote in a letter to Eli Siegel: “We have never met, and yet you have changed my life…I am more comfortable in my own skin…Thank you.”

“The Apartment” Can Teach Us about Sureness

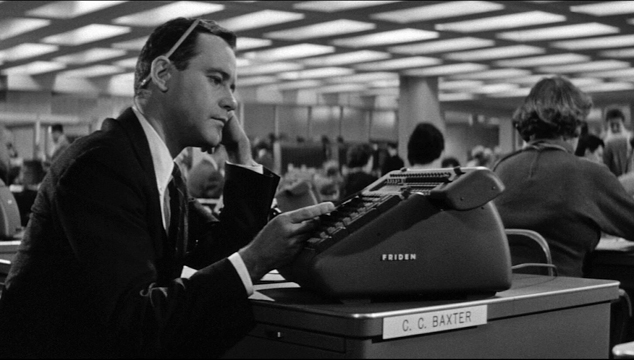

The 1960 movie “The Apartment” by Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond shows the fight in a man between going after what he thinks will make him confident—a big promotion at work—and having a purpose that makes him truly sure of himself: to know and strengthen other people.

Jack Lemmon plays C.C. “Bud” Baxter, an accountant in an insurance firm who, though seemingly compliant and mild, is ambitious and calculating. Like me of once, Baxter looks at people in terms of how he can use them to get ahead. In a lecture, Mr. Siegel explained:

The economics of the moment says: get yours. It is hard to see how a deeply tranquil attitude towards other people can arise and be maintained while a person is driven to be in constant economic combat with those people.

Baxter is anything but “tranquil.” Jack Lemmon, the late, very fine actor, plays him wonderfully as a mingling of nervous agitation and a pervasive flat, dull ache. He is cocky and arrogant one moment, wobbly and unsure the next.

When we first meet Baxter he’s working in the towering home office of Consolidated Life of New York, desk #861. He often stays late because, as he says, “I have this little problem with my apartment.” The problem? Four of Baxter’s supervisors are using the apartment to have rendezvous with lady friends, stringing him along with promises of a promotion.

For instance, Mr. Kirkeby uses the apartment one night, leaves, and Bud finally goes home. But Kirkeby returns for something he forgot, and there is this dialogue:

Bud. Mr. Kirkeby, I don’t like to complain—but you were supposed to be out of here by eight.

Kirkeby. I know, Buddy-boy, I know. But those things don’t always run on schedule—like a Greyhound bus.

Bud. I don’t mind in the summer, but on a rainy night…

Kirkeby. Sure, sure. Look, kid—I put in a good word for you with Sheldrake, in Personnel.

Bud. (perking up) Mr. Sheldrake?

Kirkeby. That’s right. We were discussing our department — manpower-wise—and promotion-wise—and I told him what a bright boy you were. They’re always on the lookout for young executives.

Bud. Thank you, Mr. Kirkeby.

Kirkeby. You’re on your way up, Buddy-boy. And you’re practically out of liquor.

Bud. Yes, Mr. Kirkeby. You still owe me for…two bottles.

Kirkeby. I’ll pay you on Friday. And what ever happened to those little cheese crackers you used to have around?

Here we see Baxter alternately inflated as Kirkeby talks of his being an executive on the rise, and then yanked down with the request for “those little cheese crackers.” But Baxter puts up with it from Kirkeby and the other supervisors, in fact he thinks it’s smart. He says later about one of them, “[He] wasn’t using me—I was using him.”

Also working at Consolidated Life is Fran Kubelik, the elevator operator, played by Shirley MacLaine. Fran is lively, pretty and smart, and Bud likes her. One day he gets a call to go up to the office of Mr. Sheldrake, Director of Personnel, and Bud thinks it’s his big day—he’s going to be promoted. As he gets on the elevator he says boastingly to Fran:

Bud. Drive carefully. You’re carrying precious cargo — I mean, manpower-wise…I’m in the top ten—efficiency-wise—and this may be the day—promotion-wise.

Fran. You’re beginning to sound like Mr. Kirkeby already.

So Fran is a critic of Bud, and she is kind.

In the meeting, Mr. Sheldrake makes it clear he wants to use Bud’s apartment, too, and Bud hands over his key. Little does he know that Sheldrake, who is married, plans to use the apartment to be with Fran Kubelik.

A Man Learns How to Be Rightly Sure

Steve Kelson is a college student who lives in Manhattan. He has a sociable manner, but told us he felt unsure within, especially with women. In one consultation, he said he’d just come from a coffee shop and, as he put it:

Steve Kelson. I was sitting there and at two tables there were very pretty women. And I was getting really tense. I didn’t feel comfortable.

Consultants. What do you think is the cause of this?

Steve Kelson. I’m not sure about that. If they wouldn’t have been so pretty I probably wouldn’t have cared so much.

“Do you think pretty women are people?” we asked. And then we asked something that Aesthetic Realism shows can have a man more sure of himself as he thinks about women:

Consultants. Do you think they have questions that are the same and different from your own?

Steve Kelson. No, I didn’t think that—I just thought they were pretty and they looked confident.

Consultants. Could a person look at you and say, “he looks confident,” and not know all the things that go on inside you?

Steve Kelson. Yes.

Aesthetic Realism explains that for a man to be honestly sure of himself, he needs to have a good kind of unsureness, to question himself: Is my purpose to respect or have contempt? Consultations meet that hope in a man centrally, and it is a privilege to see the effect they have on a man’s life.

In a class some years ago, at a time I was feeling very unsure in relation to a woman I was seeing, Ellen Reiss articulated questions I could ask myself as I thought about her: “Am I interested in this person in order to have her life stronger? What does that mean? As I think about her, do I feel deep and sweet and strong?”

It makes me very grateful to be able to learn more about that each day in my marriage to Meryl Nietsch-Cooperman. Knowing Meryl, how she meets the world and her perceptions about things, including me, makes me more myself, and I love her.

In the consultation I’ve been quoting, we told Mr. Kelson:

If you really want to know a person, and want her to be stronger, you will feel more at ease, more sure of yourself, and the reason is that you’ll be trying to have good will.

Sureness and Unsureness about Love

In “The Apartment” Bud Baxter gets his promotion and his own office. He buys a new bowler hat, the “junior executive” model, and thinks he’s on his way to the top. But Baxter is still unsure—he’s embarrassed to wear the hat, and walks around like a lonely shell.

In a class some years ago, when I spoke about how I was driven to make money and buy things for myself that I didn’t really need, Ms. Reiss asked:

If a person made a lot of money but wasn’t kind, would he feel sure of himself? Will a person ever feel sure of himself if he doesn’t have good will?

The answer I have seen, is no, because what Aesthetic Realism shows is the ethical unconscious in a man won’t let him get away with anything less than being fair. All the goodies he buys for himself will never fill the void.

A dramatic turn of events in “The Apartment” brings up a debate that Eli Siegel describes when he writes:

Two possibilities of man may be in a deep and intense fight. We all of us can find ambition and love at odds in ourselves. The desire for [love] can be hostile…to a desire to make a lot of money. Our possibilities do clash.

Fran Kubelik is with Mr. Sheldrake one night in Baxter’s apartment, and when he leaves, she is very distressed and against herself for seeing this married man. She finds sleeping pills in the bathroom and takes them. Bud comes home, thinks Fran has fallen asleep on his bed, and angrily tries to wake her up, telling her to get out. But realizing the gravity of what has occurred, he runs to get a neighbor who is a doctor, and they work through the night to save her life. When Fran wakes up she tries to get out of bed, and says:

Fran. I’m sorry, Mr. Baxter.

Bud. Miss Kubelik—you shouldn’t be out of bed.

Fran. I’m so ashamed. Why didn’t you just let me die?

Bud. Miss Kubelik, you got to promise me you won’t do anything foolish.

Fran. Who’d care?

Bud. I would.

As they talk, Bud finds himself wanting to have a good effect on her, and you feel he really cares about someone else.

He prepares dinner for Fran and himself, and in a memorable moment, takes a pot of spaghetti off the stove, picks up a tennis racquet and uses it to strain the spaghetti, humming happily all the time.

Later in the movie, we see that Bud’s earlier dream has come true—he’s risen in the company and has a cushy office. But when Sheldrake tells Bud he’s going out with Fran Kubelik again and will need his apartment, Bud refuses. Sheldrake says:

Sheldrake. Baxter, I picked you for my team because I thought you were a bright young man. You realize what you’re doing? …Normally it takes years to work your way up to the twenty-seventh floor — but it takes only thirty seconds to be out on the street again. You dig.

Bud. (nodding slowly) I dig.

Sheldrake. So what’s it going to be?

Bud reaches into his pocket, pulls out a key, and drops it on the desk—but it’s the key to the executive washroom.

Bud. The old payola won’t work any more. Goodbye, Mr. Sheldrake.

When Fran learns what Bud has done, she runs to be with him, and as they sit on the couch together, you feel Bud has a happy confidence that’s new.

Through the study of Aesthetic Realism men everywhere can learn to have one of the most valuable things in life—an honest, deep sureness.