The question “Can I be strong and kind at once—and do I want to be?” is huge in the life of every man. I wanted to be a kind person, but when push came to shove, I thought being kind was sappy and made you soft. It was a donation that wouldn’t get you too much.

To be strong and get what you wanted, I felt you had to be strategic and smart. In seventh grade, on the morning of the election for class president, I passed out candy thinking this would boost my chances for victory; but my classmates saw through my obvious scheme and I went down in defeat.

Aesthetic Realism explains the purpose that enables a man be strong and kind at once. It is good will, “the desire to have something else stronger and more beautiful, for this desire makes oneself stronger and more beautiful.” When a man has real good will he is at his keenest—he’s using his mind, his intellect, to have a good effect on people. I was thrilled to hear Eli Siegel’s conviction when he said in a lecture that kindness is “the most avant-garde virtue of them all!”

Kindness Is Relation

In his lecture Mind & Kindness, Mr. Siegel explained that the idea of “kinship” is in the word “kind.” He said:

Deep in the meaning of the word kind is a feeling that through being born there is a relation to everything… To be kind means that you want good things to happen to what is like yourself. The next question is, is there anything that is in no way like ourselves? I would say there isn’t.

I grew up in Miami, Florida and used our family’s good fortune to be a terrific snob—to feel unrelated to people, better than them. We had a Cadillac in the driveway; other families had “ordinary” cars. I was convinced my mother—and our family by extension—had the best taste in the neighborhood. Meanwhile, I had no clue that my father was often in agony about finances and providing for a family of five.

I learned from Aesthetic Realism that the very thing I thought would make me strong—building myself up thinking I was better than others—was contempt. That is exactly what makes a man weak, because our deepest desire is to like the world, to know other people and be fair to them. When a man doesn’t have that purpose, he pays the price, and I did. I often felt separate from people, agitated, and even as a boy had a lot of trouble sleeping.

A place I felt at my best was in dancing. Each week, children went to dancing classes where we learned the fox trot, the cha-cha, and one of my favorites, the waltz. Holding a girl in my arms, I felt I could have a good effect on her, could be both firm in taking the lead, and also thoughtful of her as we turned gracefully around in that beautiful 1-2-3, 1-2-3.

But my usual notion of strength was very different. I thought everybody was out for themselves, and while trying to appear like a nice guy, inwardly I thought you had to be calculating and shrewd to get your way. Years later in an Aesthetic Realism class, Ellen Reiss described accurately and humorously my approach when she said I was “Bennett-what-will-benefit-me.” When a man is looking at other people with that purpose, he cannot like himself.

Strength and kindness are related to other opposites in men, such as toughness and feeling. These were in a stir in me when the Aesthetic Realism Theater Company was rehearsing some years ago for a production of Eli Siegel’s great lecture on Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. I had a pronounced tendency to play Huck as a tough kid. When I asked about this in a class, Ms. Reiss said about Huckleberry:

He doesn’t want the wool to be pulled over his eyes and at the same time he wants to be true to everything romantic. Do you have a hard time putting the two together? Your toughness, street-wiseness and calculation is not at one with your sense of awe.

That was true. Then Ms. Reiss put in a sentence the two things that had fought in me: “You are a keen, sharp person, but you also want to see a sunrise.”

Again, so true! In this discussion, I also learned about strength and kindness in love. I was seeing Meryl Nietsch and I was very taken by this lovely woman from Long Island. The more we talked, the more I wanted to be with Meryl. But then I would focus on what I perceived as a flaw in her. Ms. Reiss asked:

Ellen Reiss: Do you think your suspicion of Miss Nietsch is at one with your big feeling about her?

Bennett Cooperman: No. An instance of where I was suspicious–the other day we were talking on the phone about Ms. Nietsch’s budget.

ER: The way you say that, everybody’s trembling.

BC: I was sure she didn’t want to see something. Then that night when I went to her house, she opened up the door and handed me the budget all typed up. I couldn’t believe it.

Ms. Reiss then asked this crucial question: “Have you hoped to be suspicious of Ms. Nietsch?” The answer was yes, and I’ve seen that determination in a man makes him cruel. You cannot be kind when you’re on the hunt for something not to like in a person. It makes love impossible, and always ends up making a man feel mean, wobbly, uncertain—anything but strong.

I’ve gotten an education about strength and kindness from Aesthetic Realism that is real gold and it’s changed my life profoundly. That includes my marriage to Meryl, who is now an Aesthetic Realism Consultant and whom I love very deeply. I cherish talking with her, trying to know her and learn from her, holding her in my arms.

Strength & Kindness in a Song & Dance Man

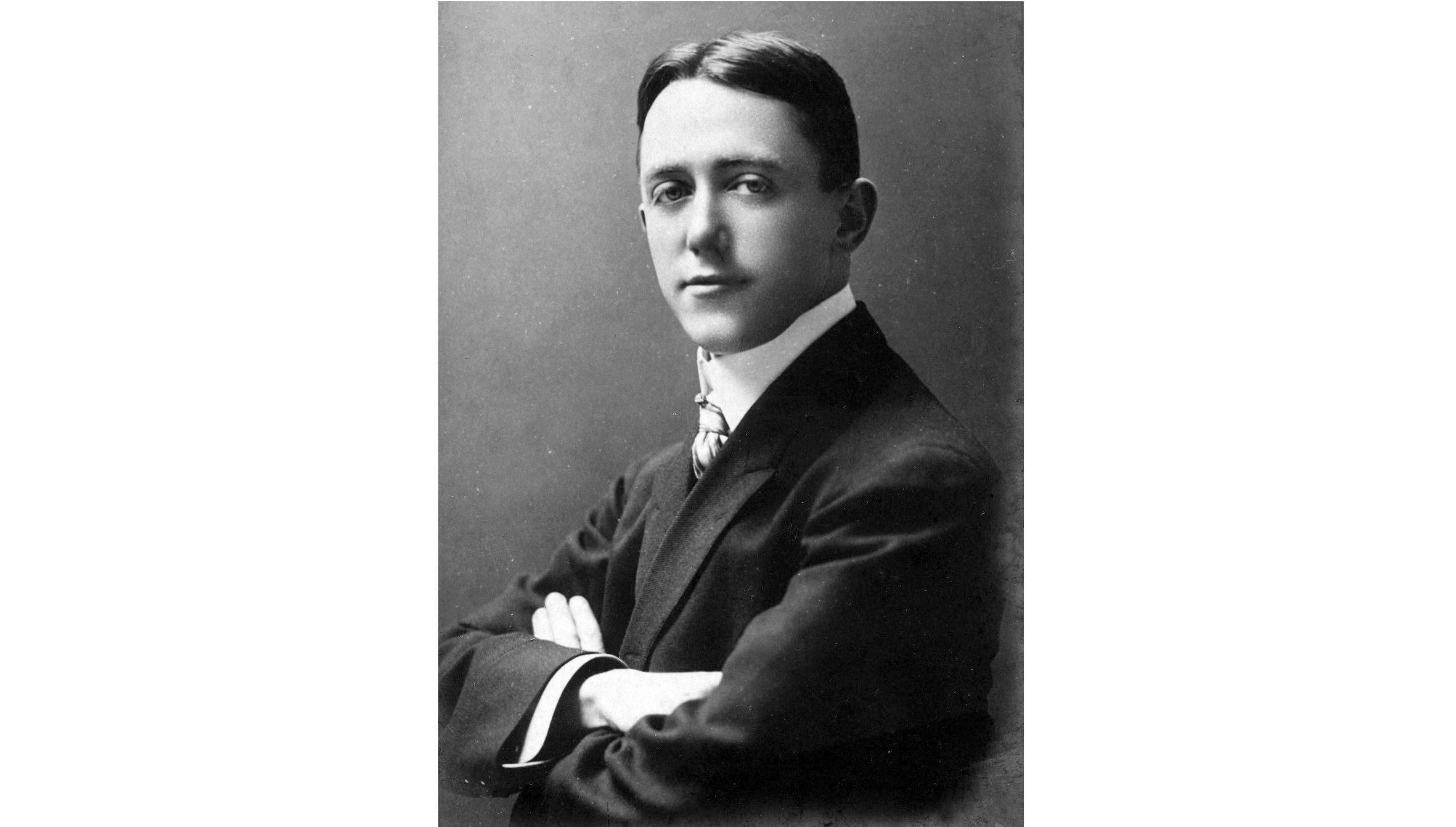

I speak now about aspects of the life and work of George M. Cohan—singer, dancer, actor, song writer, producer—because he can have us understand better what real strength and kindness are, and what interferes. From the early 1900s, Cohan had one hit after another on Broadway. Writes Ward Morehouse in George M. Cohan, Prince of the American Theater:

Into the new-century picture came the bounding and brassy George Michael Cohan…with a tempo and style all his own…George M….prepared to show Broadway and the whole wide world that he was the smartest little guy…who ever did the buck and wing and climbed the proscenium arch.

The noted drama critic Alexander Woolcott said Cohan’s “abiding purpose is to entertain royally,” and that’s just what he did, including through writing some of the most loved songs in the American songbook, including: “You’re a grand old flag, you’re a high-flying flag, and forever in peace may you wave…”; and “Give my regards to Broadway, remember me to Herald Square…”; and “I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy, A Yankee Doodle, do or die. A real live nephew of my Uncle Sam, born on the Fourth of July…”

Eli Siegel defined kindness as “that in a self which wants other things to be rightly pleased,” and this was, I believe, an intense impulsion in Cohan when it came to the theater, where audiences were thrilled by the pizzazz and depth, comedy and sentiment, raucousness and grace in a Cohan show.

But all his life, that kind impulsion in Cohan battled with a false, aggressive notion of strength that made him mean, and, I think, caused him to have great sadness. “He was a lone-wolf,” writes Morehouse, “a brooder.”

George M. was born in 1878 into a theatrical family, making his stage debut at four months old with Jerry, his father, Nellie, his mother, and his sister, Josie. They became known as The Four Cohans, troupers in the vaudeville circuit.

A moving account shows the little boy, George, wanted to be kind. “He wept at the sight of beggars or the infirm,” writes biographer John McCabe. His mother, Nellie, tells how George would put all his coins in his pockets:

He would start up the street for a walk…thoughtfully but observant. ‘What are you looking for, Georgie?’ we would ask him. ‘Poor old people,’ he would answer. If he saw any, he divided…his money among them.

That impulse came from something so different than what developed in Cohan over the years. In his early teens, he became the bane of theater owners and stagehands with whom he fought ferociously about every aspect of a show, convinced he was right and everyone else was wrong. He sometimes caused such a scene that he got his family fired. Morehouse says he was cocky, pugnacious and belligerent throughout his life.

Men have equated fighting with being strong, and sometimes a fight is necessary. For example, life in vaudeville was tough and performers were often treated badly. Cohan felt he had to be combative to take care of his family. He said of his father:

His quiet, gentle manner, and the way they used to take advantage of [him]…taught me that aggressiveness was a very necessary quality…

But the question is—and this goes for men today—did something in him relish doing battle in a way that went beyond what was necessary? Did he equate strength with beating out others? I believe he did, and this made him greatly unsure.

George M. eventually achieved his dream of bringing The Four Cohans to Broadway. And he became one of the earliest to create a new form: The full-length musical, with songs that were integral to the plot. These shows had a new speed, a new snap. At the turn of the 20th century, Cohan’s shows began a shift on Broadway from elegant operettas and European entertainments with a dignified pace to musicals with bustle and energy, a feeling of New York life. There was a new relation of opposites in a Cohan show, opposites akin to strength and kindness: assertion and tenderness, force and grace. There were comic scenes, banter that poked fun at politicians, lively dances; and then lyrical ballads with honest sentiment—and audiences loved it.

What a Man Learns in Consultations

David Hughes leads a team of IT developers who work on new software. At 27, he’s gone far in his career, yet, he said, “A lot of things are going on in my life.”

In a recent consultation, he said he preferred not to think too much about other people. “It’s a lot easier that way. Like, I don’t want to be bothered with that,” he said. We asked:

Consultants: What does a person get by having feeling, being kind to other people?

David Hughes: I don’t know. I don’t know. That’s something I’ve never spent much time thinking about.

Cons: That’s right. Most people feel the answer is “nothing.” “I’ll get things by working on my own behalf—period.”

DH: I don’t think you can always see something tangible out of caring for others. And I am very results-driven.

Mr. Hughes’ girlfriend, Jenny, has a large interest in social justice, and she’s criticized him for being selfish. He was pretty courageous when he said plainly, “It’s hard for me to care so much about random people I don’t know who can’t provide me with anything.” We asked:

Cons: Do you think one of the things you would get would be self-respect?

DH: Yeah.

Cons: Do you think every person is judging himself all the time?

DH: I know I am.

Cons: That’s right. We have what Aesthetic Realism calls an ethical unconscious. Something in you feels you are making a mistake in how you see the world. There’s a self in you saying, “This is not going to work. It’s not in behalf of your strength.” You may have a great job, you may have good health, a good family, a nice girlfriend, but something is missing. Do you feel that?

DH: Yes.

Later, we asked Mr. Hughes whom he admired in history:

DH: I would say Franklin Delano Roosevelt or Muhammad Ali.

Cons: Good. What quality did they have that you care for?

DH: Um… their ability to get things done.

Cons: That may be true, but do you think the two people you chose are right on the subject we’re talking about? Do you think both of them had feeling for people in a big way?

DH: Definitely. Those are two perfect examples.

Cons: It’s so interesting—you’ve been talking about not wanting to feel too much about others, and you picked those two.

DH: It’s ironic!

Cons: Franklin Delano Roosevelt was born very fortunately. He never had to do anything. But he said the hell with that, I’m going to use my life to take care of the suffering of people. And in his presidency, he created many programs that helped people. We still have Social Security. He had flaws like everybody, but there was a feeling for people.

DH: Yeah.

Cons: Muhammad Ali didn’t go into the Viet Nam draft because it was against his principles. That was really a saying, “I won’t let myself be used in behalf of unkindness to people.” As a sports fan, you know he missed years as a boxer when he could have been great. He was courageous.

DH: He was.

We asked Mr. Hughes:

Cons: Do you judge yourself on the same basis as you judge them?

DH: Well, I’d like to think it’s on the same basis, but it’s probably different. I judge them for definitely caring for others and I don’t judge myself at all with that.

Cons: Yes, you do! And that’s the best thing in you. When you’re trying to have a good effect on another person, that’s when you are most successful.

Strength & Kindness in Love

George M. Cohan was married twice, first to Ethel Levy, a singer and comedienne he met at 21. She was a critic of him and “stood up to George if she thought he was wrong, and this was not infrequent,” says Morehouse. I think, like men today, Cohan wanted a woman to soothe and serve him, and the marriage ended after seven years.

Cohan’s second marriage was with Agnes Nolan, a chorus girl in one of his shows. Agnes quit the stage after marrying Cohan and remained with him until his death in 1942.

From accounts I’ve read, it seems Cohan wasn’t comfortable thinking deeply about a woman, didn’t see it as strong to try and be kindly within the depths of who she was. He’s often described as a “man’s man,” and it was said “men got to know him better than women ever did.”

Cohan’s way of seeing women affected his work as a playwright, too. Morehouse says his women characters “were usually on the sappy side—superficial, sugary, and in contrast with some of the vital and crackling roles he wrote for men.”

I feel very lucky as a man to have heard questions from Ellen Reiss about love that changed my life. Some of them are:

- Where do you feel stronger, being swept by Meryl Nietsch or feeling you can take her or leave her?

- Which would you rather be lost in, the television or Miss Nietsch? There’s the line from Tennyson’s poem The Princess—“So fold thyself, my dearest, thou, and slip / Into my bosom and be lost in me”—do you like that idea?

- As I was thinking about a woman she said I should ask: “Am I interested in this person in order to have her life stronger? What does that mean?”

Strength, Kindness, & the Actors Equity Strike

A huge happening in the American theater was the Actor’s Equity Strike of 1919. Before this strike, actors were required to give hundreds of hours of unpaid rehearsal time, and contracts could be broken at the producers’ will. Actors paid for their own travel and costumes. Once a show opened and was a solid hit, actors were let go and replaced with less expensive talent.

In 1919, the professional theater was the fourth largest industry in the nation. And so, it was a tremendous event when the actors walked out on the evening of August 7, closing more than half of the shows in New York. Musicians, stagehands and others joined them, and the strike spread to other large cities.

The loudest voice against the strike was that of George M. Cohan. He took it personally that the strike closed a hit show at his Cohan Theater, and immediately co-founded and became president of the anti-strike Actors’ Fidelity League. “I’m going to fight everybody who’s against me,” he said. Morehouse writes that Cohan was determined “to defeat the friends of a lifetime, his fellow actors.”

Cohan’s notion of strength, which he had all his life, led him to make vicious choices at this time. Although he was known to pay his actors well and treat them decently, he felt he was the man in charge of his shows and no union was going to tell him what to do—ever. “His argument,” writes Morehouse, was “with the entire idea of unionism.”

Unions, I’ve learned, are a beautiful oneness of strength and kindness because they fight to have people treated fairly. A large part of my education has been performing in Ethics Is a Force! Songs about Labor—a show The Aesthetic Realism Theatre Company has presented at union events around the country. It has been the honor of my life to be in the cast of these historic presentations, standing next to the American labor leader and my dear friend, the late Timothy Lynch, President of Teamsters Local 1205. I learned then and still do from his passion and logic, his joie-de-vivre.

The Actors Equity strike was settled in one month, with the actors getting everything they demanded. But Cohan remained an “Equity-hater” for the rest of his life. He split from his partner of 15 years, Sam Harris, who was on the side of Equity. Morehouse says the strike “changed…his outlook on life immeasurably” and that though Cohan performed for years afterward, “His withdrawal…from life itself…began at the time of his overwhelming defeat by Equity.”

We can ask, why—why did this affect Cohan so centrally? I think his own choices, to squash kindness in himself and make himself tough, hard, and immovable, affected him greatly. “He lost more than the Equity strike in 1919,” writes John McCabe. “He lost heart.” I take that to mean he lost the thing in him which stood for feeling, for real kindness.

My inspiration for writing about Cohan was hearing a tape-recorded lecture in which Eli Siegel discussed poems by the American entertainer George Jessel. One was a soliloquy of Sam Harris, Cohan’s partner. Mr. Siegel felt the lines were close to being poetry and he did a “linear reworking” to make them truly poetic. Here are some of the lines:

One night, in Chicago,

I met George M. Cohan,

The greatest talent of all.

We became partners.

He wrote our plays; acted

In our plays.

I attended to

The business things…

What I added

Was my love for him.

There was hit after hit for us.

We went together everywhere…

When he married

An Irish girl with loveliness,

Look, I married her sister.

Then the poem shifts to the break up:

All of a sudden,

We were friends no longer.

In 1919,

The actors went on strike…

I couldn’t convince him

They were right,

And we should be with them.

He couldn’t see they had been abused

By unfair managers…

God, I missed him!

How it hurt

Not seeing him,

Not talking to him—

Not to be in the sunshine

Of his great talent.

A Song with Good Will

That great talent, and a beautiful oneness of strength and kindness, is in perhaps Cohan’s most popular song, “Over There.” When America declared war against Germany on the morning of August 6, 1917, Cohan “sat down at his desk, took a pencil, and began [writing]. There was a new melody in his head.” Within an hour, he had written “Over There.”

The song was immediately being sung all over the country and it gave courage to the troops. Though the justice and rightness of World War I can be questioned, this song has good will because it’s a saying that what is not oneself, what is “Over There,” is something we should encourage, strengthen. Here is George M. Cohan himself singing “Over There” in a 1936 recording.

Audio PlayerMen everywhere deserve to know the education that can make them strong, kind, and happy.